Why aren´t radical voters more satisfied with democracy when entering the political system? The role of affective polarization

This text follows the presentation of the paper “Radical party entry and satisfaction with democracy: experimental evidence from the 2022 French presidential elections”, at the workshop “New Challenges to Democracy”, organized at the Station de Biologie des Laurentides, Université de Montréal, 12-14 September 2022

Prior research shows that voters tend to become more satisfied with democracy following elections, even if they lose. Yet, recent evidence suggests that populist and radical voters become even less satisfied unless winning. Using experimental and qualitative evidence from Éric Zemmour voters during the 2022 French presidential elections, Álvaro Canalejo-Molero and Morgan Le Corre Juratic show that these voters’ satisfaction with democracy decreases because election results boost their level of affective polarization. Following elections, radical voters focus on the out-group party victory rather than their own party entry into the system.

Following the Eurozone and Refugee crises, European party systems have experienced drastic shifts, involving the collapse of mainstream parties and increasing fragmentation. Building on anti-system rhetoric to mobilize on citizens’ grievances against political elites, new radical and populist parties, such as the Italian Lega and Fratelli d’Italia, Vox in Spain, or the German Afd, have spread over Europe.

While much of these parties’ political stance relies on anti-system platforms, some of them have been extremely successful in the past elections, managed to enter parliament, and even started to govern using the once criticized institutions. Now that these parties’ voters gained representation, how do they evaluate democratic institutions? Can their electoral success reconcile them with democracy and boost their overall satisfaction with the system?

While prior research suggests that elections should boost satisfaction with democracy, even among losers, recent findings suggest that this is not the case for populist and radical voters. Our working paper addresses these contrasting findings by assessing not only how radical voters react to their own party success but to the out-group party victory.

Most research analyzing the effect of elections on satisfaction with democracy put a large emphasis on voters’ evaluation of their own parties’ performance. Building on this theoretical framework, voters are expected to develop some satisfaction with the system even when losing elections. The idea behind this argument is that voters benefit from participating in elections itself. At the bare minimum, they experience the emotional reward of meeting a civic duty and become more satisfied the better the results of their party. However, recent research at the aggregate level does not confirm this finding for populist and the most radical voters. In our working paper, we argue that this literature overlooks an alternative identitarian mechanism, where polarized voters of radical parties not only focus on their own party performance but also the out-group party success. Our research tests this argument using the recent emergence of Éric Zemmour during the 2022 French presidential elections as a natural setting for a survey experiment.

We recruited French radical right voters using Meta ads and assessed their change in satisfaction with democracy and affective polarization before and after the first round of the presidential elections. The French case enabled us to build on the uncertainty regarding the power potential of Éric Zemmour in the national assembly and as a coalition partner (in the case of Marine Le Pen’s victory) following the first round. In our study, we manipulate the perceived in-group (Zemmour) and out-group (Macron) party success following the first round of elections and assess changes in satisfaction with democracy and party ingroup/outgroup affects. More precisely, in a vignette experiment describing the four first candidates, we manipulated the emphasis of the coalition (T1a) or assembly representation (T1b) potential of Éric Zemmour’s party, against the emphasis on Macron's likely victory in the second round (T2).

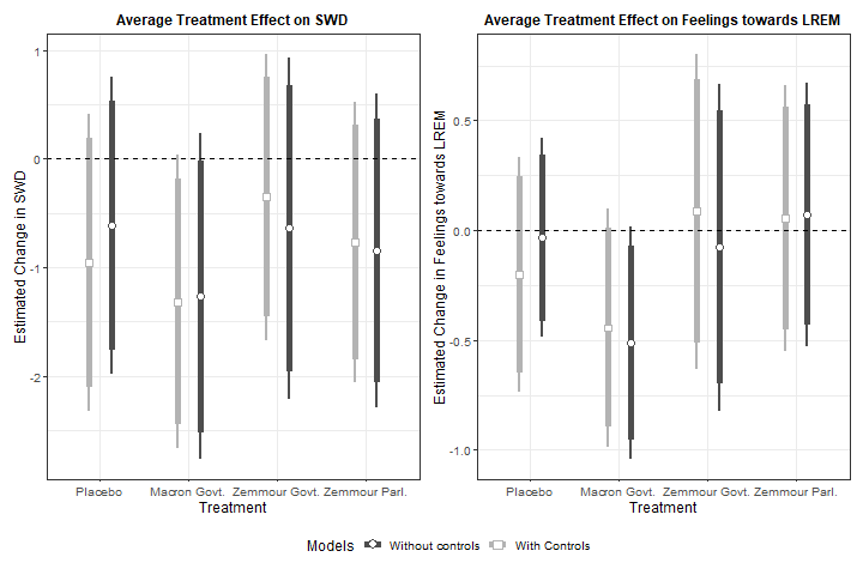

Our study shows that elections matter not only as a signal of the in-group party but the out-group party’s performance, which is highly consequential for radical voters. The plot in figure 1 visualizes the results. When Zemmour voters are reminded that they may play a crucial role in the National Assembly, they do not experience any significant change in satisfaction with democracy. The same happens when they are framed with the possibility that the second-round winner, implicitly Marine Le Pen, includes their candidate in the governing coalition. Instead, when these voters are told that Macron could win the election again, they display much lower satisfaction with the system. It is important to notice that the experiment participants completed this survey just a few days after the first round, so the 2nd round outcome was highly uncertain. Still, highlighting the out-group good results had a much larger impact on their evaluations of democracy than emphasizing their own party success.

Figure 1. Average treatment effect of frames about the election results on changes in satisfaction with democracy

Note: Average treatment effects and 90/95 percent confidence intervals based on ordinary least squared regression models.

Furthermore, we also measured the effect of each frame on the respondents’ feelings toward Macron’s party Le Republique on Marche! Again, the frames that emphasized the good results of Zemmour did not have any significant effect, neither positive nor negative. In contrast, those respondents exposed to the frame highlighting Macron’s likelihood to govern reported much more negative feelings towards Macron’s party. In a nutshell, the idea that Macron could win the election outweighed the possibility that Zemmour played an important political role in democratic institutions. Not only did it foster dissatisfaction with the system but also negative feelings against the mainstream out-group.

We further confirm these findings by conducting a qualitative analysis of open-ended questions on respondents’ evaluation of elections. Surprisingly, even if Éric Zemmour outperformed both mainstream parties (the Socialist and the Republican party) in its first election, almost no respondent mention their own party success. Most answers have a negative tone, focused on Macron’s victory, together with emotions displaying high levels of affective polarization. Respondents express anger and disgust toward the mainstream party out-group and link this affective response with a negative evaluation of the democratic system and elections. As the two following excerpts illustrate, the possibility that the out-group party wins make them question the elections’ legitimacy.

R1: “I am disgusted that Macron is in the second round of the presidential election after all the dirty deals he has done.”

R2: “Rigged non-democratic election confiscated by the media subjected to the billionaire friends of Macron”

Overall, these findings suggest that polarized voters outweigh any potential positive effect of their in-group party success by the mainstream out-group party victory. This mechanism leads radical voters to become more dissatisfied with democracy, even following their party's entry into the political system.

These findings pose concerning implications for democracy. Some scholars and observers have trusted that anti-system voters could recover some confidence if these parties become regular participants in the democratic game. The assumption behind this expectation, however, is that voters are satisfied enough with their results at the polls. Yet, if entering the system is not perceived as a positive outcome of elections but fuels affective polarization and dissatisfaction instead, the hope that democracy self-reinforces is compromised. Policy efforts should be directed to reconcile radical voters with the important benefits of having a voice in institutions. Future research may provide clearer guidelines on how this goal could be achieved.