Venom and vessel: Intersections of arts and sciences

The project team reveals more.

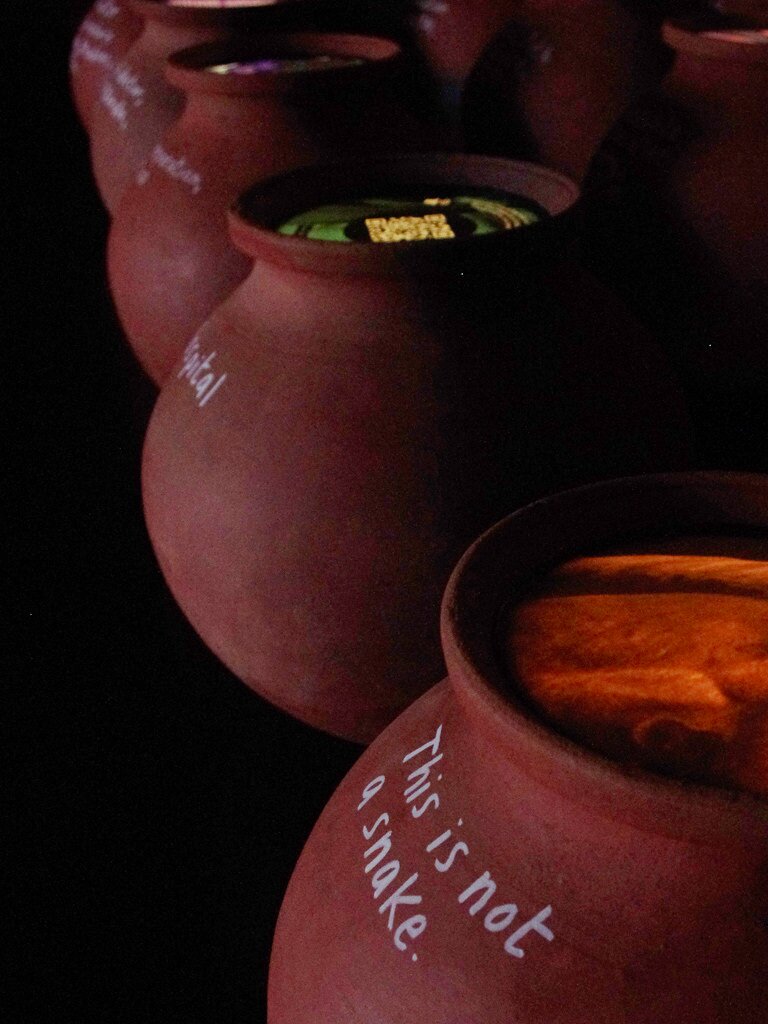

In a small village in southern India, every day during the hunting season dozens of Adivasi villagers from the Irula community (categorised as a ‘tribal’ population) bring some of the country’s most dangerous snakes, such as cobras, vipers, and kraits, to a community-run venom collection centre, the only one of its kind in India. Hundreds of snakes are kept in simple clay pots, stored in a pit for several weeks while their venom is extracted, and then released back into the wild. The venom then undergoes a series of operations: It is refrigerated, purified, and freeze-dried, before being sent to pharmaceutical companies, where it is injected into horses for several months to develop their immunity to envenomation. The horses’ antibodies are then used in the production of antivenom serum, a vital medication.

The venom then undergoes a series of operations: It is refrigerated, purified, and freeze-dried, before being sent to pharmaceutical companies

Envenomation, as seen through the eyes of the Irula cooperative, raises a series of questions for the natural sciences, the social sciences, and the visual arts: How can we describe the process of producing antivenom, from the capture of snakes to the injection of serum into patients? How can we explain the concepts associated with venom, based on the different social and professional positions of the groups involved—from scientific researchers to the Irula communities? How can traditional knowledge, myths, and ritual practices associated with snakes and venom in India be integrated into this understanding, and how do they connect to the history of socio-biological relationships between humans and snake species? To what extent do the contrasting conceptions reflect the convergence of contradictory worlds and ontologies? Finally, how can we account for research processes through ‘sensitive’ methods? What narratives or forms of storytelling should we prioritise in order to bring to life the real issues facing a society, without giving in to ethically questionable modes of calculation?

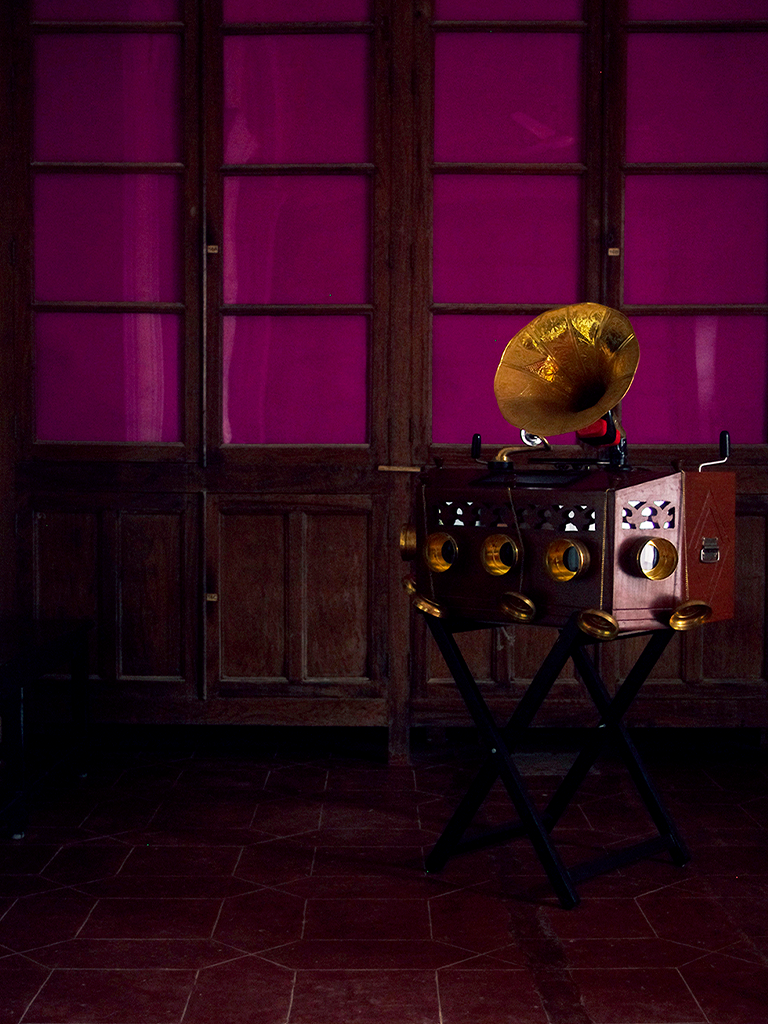

In an attempt to answer these questions, we have put together the Slithering Cures exhibition, which will be on show at the Institut Français in Pondicherry in February 2024. The exhibition, which is the result of a dialogue between visual artists and social scientists, takes visitors on an audiovisual journey through the production of antivenoms in India. At the cooperative, visitors can observe from above the venom extraction process conducted in a pit filled with jars—an atmosphere that combines the spectacular with technical explanations.

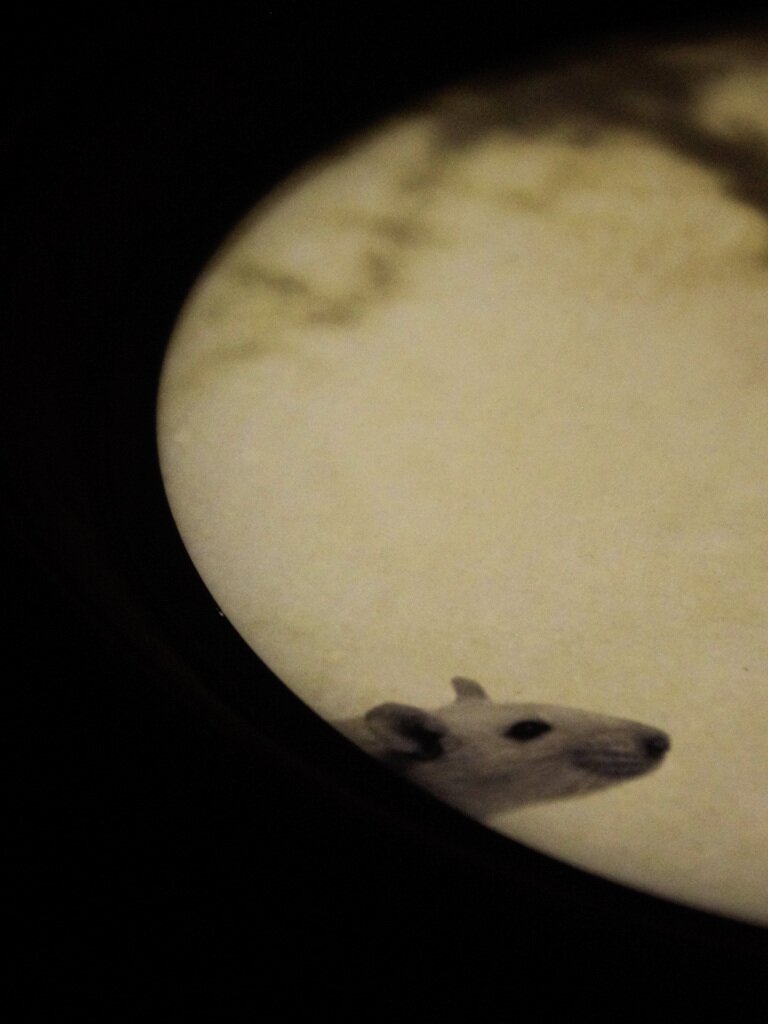

This opening scene forms the basis of a scenographic setup. The installation consists of seventy-tow clay pots arranged on a platform placed in semi-darkness. Each pot is backlit and displays an image taken from the visual collections held by the Madras Crocodile Bank Trust (which houses the venom extraction cooperative), the Institut Français de Pondichéry, the École Française d’Extrême-Orient, Vins Bioproducts (an antivenom manufacturer), the classic herpetological work The Thanatophidia of India (J. Fayrer, 1872), or the personal archives of biologist Kartik Sunagar. Sound recordings captured in the field (for example, during a snake hunt with members of the cooperative or in the animal enclosure of a large pharmaceutical laboratory) are also incorporated, as well as musical compositions created from materials related to the exhibition (for example, extracts from Indian films recounting stories of snakes, chants, and mantras intended to protect against bites). The tour is free. Visitors move around the platform, looking at the pots and selecting materials to explore visually.

Coming from different backgrounds, in both the arts and social sciences, we carried out fieldwork and conceptualised the installation in a collaborative way, without delineating or assigning tasks traditionally structured for efficiency. In this way, we nurtured the making of the exhibition in the most collective and least hierarchical manner possible, resulting in a narrative that reflected our professional differences.

Slithering Cures is thus fully aligned with the myriad experimental practices that seek to discuss global health and environmental issues and their intersection, as encapsulated in the notion of One Health, for example, while at the same time experimenting with alternative narrative forms of these stories.

Maïda Chavak, visual artist, set designer

Camille Neff, artist, installer and independent exhibition curator

Mathieu Quet, Director of Sociology Research, IRD, Ceped and project coordinator

Article published in the second issue of the Journal de la FMSH.