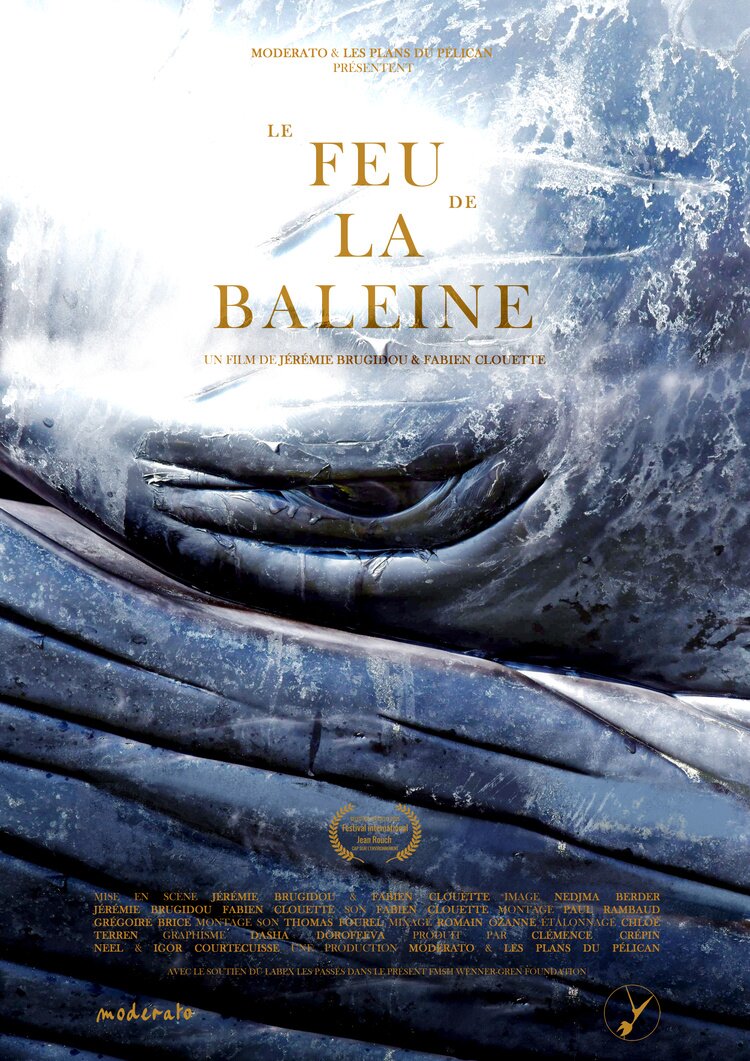

The whale's fire

Based on this premise, the Charisma project explores the shared history we have with these creatures, which hold such a special place in our physical, imaginary and social worlds. Fabien Clouette (EHESS and LESC) and Jeremie Brugidou (Imera and LESC), members of the project, explain.

Since the days of intensive hunting, whales have been bearers of fire: their oil provided light and was a fundamental resource for early industrialisation. Nowadays, this fire has mainly become symbolic and emotional: as a protected, charismatic animal, both its presence and absence move and unite people. Through making a documentary film about a few recent and notable strandings of large whales in Finistère (Le feu de la baleine, 2025), we sought to tell the shared story we have with these creatures, which hold such a special place in our physical, imaginary and social worlds. In this film, we sought out informal, scientific and cumulative knowledge to understand this complex relationship, between exploitation and fascination, which has led humans to hunt whales for centuries.

Cetology, the study of cetaceans, was first developed on the decks of whaling ships. Melville himself, in Moby Dick, evoked the difficulties of this science (the development of collective knowledge about population phenomena) in seeking to learn about the ‘variety of species’ of whales. The author, who had a background in whaling, took stock of a ‘confused’ science, marked by ‘Leviathanic fury,’ which could only fuel his narrative of one man's fantastical quest for an individualised whale.

Films documenting whaling include: Pierre Perrault, notably Pour la suite du monde (1962); Carlos Casas, Hunters Since the Beginning of Time (2008); Peter Gimbel, Blue Water, White Death (1971); and, of course, the diptych by Mario Ruspoli and Chris Marker, Les hommes de la baleine (1958) and Vive la baleine (1972). Between Mario Ruspoli's first film and the second, made with Chris Marker, attitudes had changed. The condemnation of whale slaughter since the beginning of the industrial revolution is led head-on in the 1972 film, whose voice-over is a direct address to the whale. Whaling played a crucial role in the emergence of industrialisation by providing the oil needed for lighting, before petroleum and then electricity were used. In the second half of the 20th century, the deadly legacy of whaling transformed the charisma (Lorimer 2009) of whales into melancholic charisma (Huggan 2018). Today, images of whale interactions circulate widely on social media and fuel an emotional crystallisation around these exceptional creatures.

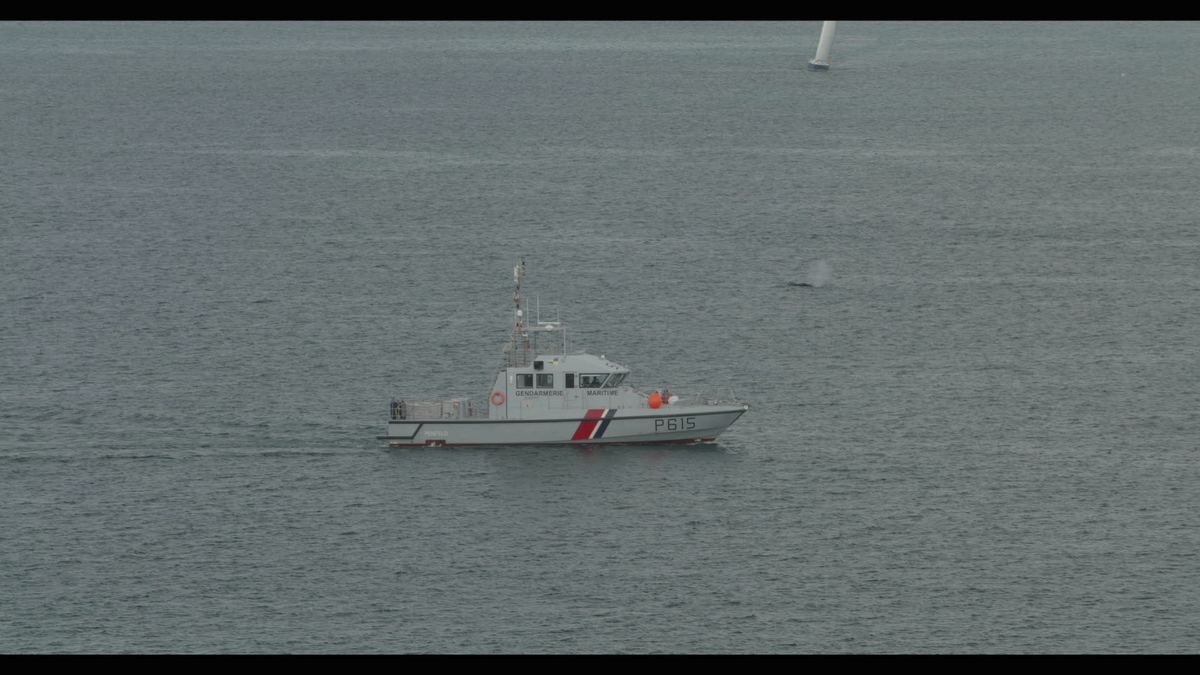

We were saddened to witness whale strandings in Finistère and to document the work of the teams responsible for refloating, analysing and cutting up the bodies. Starting with the human actions that punctuate the strandings, our film explores the current situation between humans and whales in France in a context of declining biodiversity and profound changes in the alliances between different communities of living beings. The actors who gravitate around cetaceans have varied statuses, interests and legitimacies: scientists, RNE correspondents, managers, carers, activists, tourism entrepreneurs...

Despite the common goal of protecting whales, tensions arise over the perspectives adopted, and it is often the opposition between the population and the individual that resurfaces. Should we, and can we, save a single whale at all costs? Between the cause, science and symbolism, our interventionism is called into question.

Our relationship with whales is one of consuming passion: after burning their blubber for centuries, we now burn with the desire to get close to them for just a second. It seems to us that this is the ‘fire’ that tourists are looking for, aboard boats that engage in what one captain in our field described as ‘benevolent hunting’.

Winning project 2022 of the ‘Arts’ programme

Article published in the third issue of the FMSH Journal.

Sous les temps de l'équateur. Une histoire ancienne de l'Amazonie centrale

Le coopérisme

De la rue à la mairie