The toxic afterlives of colonial collections

The issue is coordinated by Lotte Arndt. It is partly bilingual, and focuses on the Toxic afterlives of colonial collections. It presents contributions by Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, Jimmy W. Arterberry and Annette Arkeketa, Helene Tello, Noémie Etienne, Samir Boumediene, David Dibosa, Florian Fischer, Sybil Coovi Handemagnon, Anaïs Farine, Clelia Coussonnet and Minia Biabiany, Filip de Boeck and the collectif Picha (with the images of Frank Mukunday and Tétshim), Mega Mingiedi Tunga and Lucrezia Cippitelli.

The toxic afterlives of colonial collections

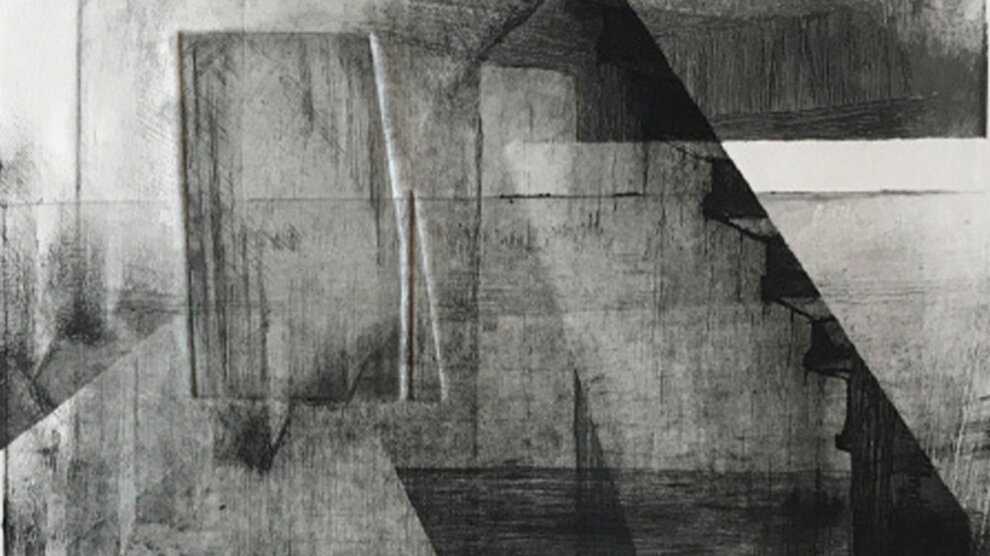

A sequence from Matthias de Groof’s documentary film Palimpsest of the AfricaMuseum (Belgium, 2019), which follows the packing and transportation of the entire collection to external storage rooms in preparation of the large-scale renovation of the Royal Museum for Central Africa in Tervuren (2013-2018), shows workers cleaning empty display cases. They are wearing white protective suits, breathing masks and nitrile gloves, a comprehensive equipment that protects them from toxic dust. Behind the glass of dioramas and display cases, which for more than a century had held objects as in time capsules, artifacts from Congo were treated with biocides to prevent material decay and insect damage. These treatments were administered for decades to extend the material life spans of the objects. The substances have for some sedimented into the materials and can still deploy agency. Their toxic afterlives can possibly interfere with the present and future uses of the artifacts, obstruct physical contact and tactile practices with them, and require the implementation of protective measures on several levels.

This journal issue is part of an ongoing research (Arndt, forthcoming) on toxic modernity and museum collections. It opens a dialogue with academic and artistic works engaging with related topics. The issue takes the collections that were constituted in a colonial context as a starting point for discussing toxicity in a double perspective. On the one hand, it refers to the material, political and epistemological consequences generated by certain conservation methods that were elaborated in Europe, and subsequently applied in many museums around the world. The practices that intoxicated lastingly some of the objects in the collections (Odegaard/Sandogei 2005) are then interrogated in the context of the modern promise of endless progress, limitless life, and boundless productivity, that colonial policies and globalized capitalism defined as the sole possible horizon (Ohman Nielsen 2015, Vergès 2017, Alampi 2019).

The contributions in the present issue situate museum collections and conservation practices developed in Europe in the history of the classification and hierarchization of living worlds (Boumediene 2016). They interrogate modern conservation practices in museums as a cultural technique emerging in Europe in the nineteenth century (Caple 2000), alongside the disciplinary structuring of the sciences and the consolidation of the opposition between nature and culture (for a critique, see Latour 1991, Ingold 2013, Haraway 2016). This technique is developed simultaneously to the transposition of objects into the museum, a place that allows the fabrication of stable conditions of preservation over time. Indeed, museification aims to extend the material life of these perishable objects made of organic materials, which coincided with their removal from the cultural environments they were part of. The journal strives to understand the practices of museum conservation and their unpredictable long-term effects in the broader context of the uses of chemicals in modern times, carried by the belief in technological progress.

This project won the FMSH 2020 call for projects Changing World(s). It is attached to the CRENAU (UMR 1563 CNRS) of the École Nationale Supérieure d'Architecture de Nantes as part of its agreement with the École des Beaux-Arts de Nantes Saint-Nazaire.

©Matthias de Groof, Palimpseste du AfricaMuseum, Filmstill, BE 2019