Do protests mobilize voters?

This text follows the presentation of the paper “Does electoral behavior change after a protest cycle? Evidence from Chile and Bolivia” (with Renata Retamal), at the workshop “New Challenges to Democracy”, organized at the Station de Biologie des Laurentides, Université de Montréal, 12-14 September 2022

The effects and consequences of contentious activities have been widely researched topics within social movements scholarship. Given that social movements are often presented as an alternative to generating changes that have not been achieved through institutional channels, special attention has been given to examining their impacts. However, how street mobilization affects subsequent electoral behavior remains a widely overlooked area.

Our research addresses the relationship between protests and elections through the examination of the contentious cycle that unfolded during 2019 in Chile and Bolivia, leveraging on the fact that elections took place in both countries the year following the protests. We add to the scholarship surrounding the effects of social movements and protests on electoral processes within democratic contexts, questioning the long-standing assumption of the backlash effect that contentious activities can have over institutionalized political participation.

We find those municipalities that experienced contentious events present an increase in voter turnout in the electoral process that followed the protest cycle. A possible explanation for this finding, based on the literature, is that protests seem to increase political efficacy: after the protest cycle, voters feel more confident regarding their capabilities of affecting the political setting. In this sense, protests serve as a mobilizer, causing individuals to develop stronger levels of political efficacy, which may contribute to more people turning out to vote.

But how much certainty can we affirm that the increase in political efficacy is the mechanism that is explaining the increase in electoral participation? We test this by using individual-level longitudinal data for the case of Chile using the ELSOC survey, an instrument elaborated by the Centre for Social Conflict and Cohesion Studies (COES). This survey is, to our knowledge, the only longitudinal survey that addresses social issues and political positions in the country.

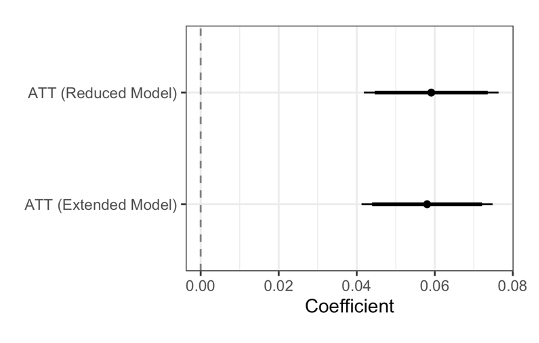

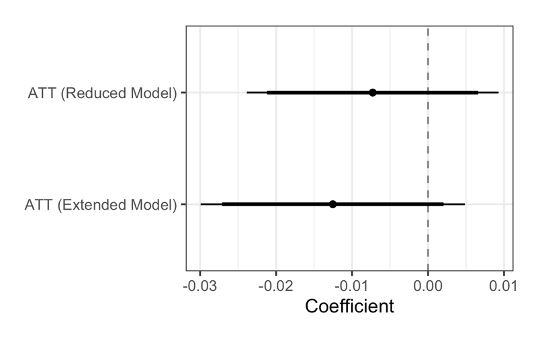

Figure 1: Treatment effect of having protests (at the municipal level) in voter turnout

Note: The dependent variable is voter turnout as the proportion of total votes from the electoral roll (for Chile). Extended model controls turnout in the previous general election and population (log)

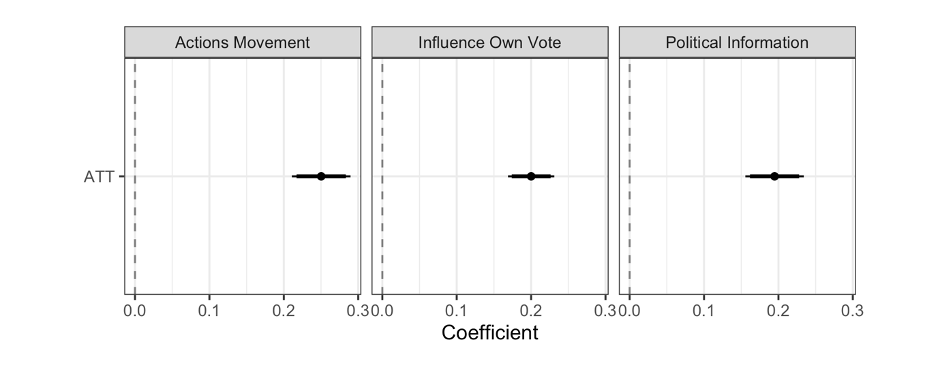

We selected three variables to measure the political efficacy mechanism: the degree of agreement that the actions of the social movement most supported by respondents are capable of generating social change, the perceived influence of one’s own vote in deciding the outcome of an election, and the self-reported level of political information in the media. This individual-level analysis corroborated the results: people who live in those municipalities where protests were held present higher levels of political efficacy, which translated into a higher voter turnout.

Figure 2: Treatment effect of living in a municipality that had protest over indicators of political efficacy

Note: The dependent variables for each panel are the level of agreement with the statement “the actions of the movement generate social change” (left panel), level of agreement with the sta

The literature on social movement has pointed out that political street demonstrations, including protests and even riots, may have the capacity to affect other individuals’ voting decisions since they act as a signaling phenomenon, making people aware of certain issues or grievances that were previously ignored or concealed. That is one reason why, when exposed to actors who voice their political discontent, citizens become more critical of the political elite’s performance.

We tested the signaling effect of protests using local-level data for Bolivia. Bolivia has had mandatory voting since 2009, which allows us to overcome the endogeneity between turnout and electoral preferences, since we can assume that turnout will not be greatly affected by external events, such as protest cycles.

We find these protests do not affect electoral preferences or lower the incumbent vote, which points to a lack of signaling effect of this type of contentious activity, i.e., their ability to make grievances salient and to attribute those grievances to the political elite.

Figure 3: Treatment effect of having protests (at the municipal level) on incumbent vote share

Note: The dependent variable is voter turnout as the proportion of valid votes obtained by the incumbent party (MAS) in the 2020 Elections in Bolivia. Extended model controls turnout in the previous gener

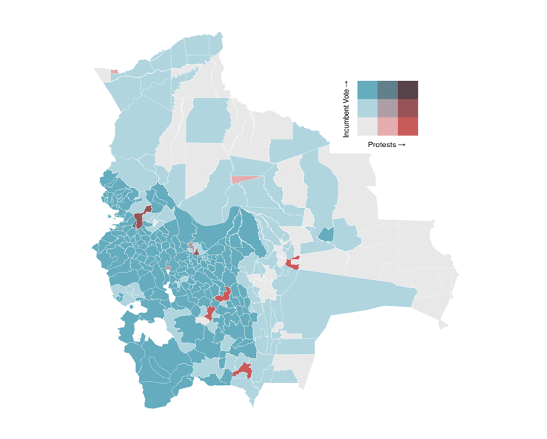

As a visual representation of this result, Figure 4 shows that there is not a strong relationship between low incumbent vote share and protests at the municipal level: those municipalities where a large number of protests took place, and at the same time, exhibited low incumbent party vote (i.e. where the signaling mechanism took place) are a minority. With this, we do not have enough evidence of a negative effect of protests on incumbent vote share due to the signaling effect of protests.

Figure 4. Protests and incumbent vote share in Bolivia

Note: Bivariate choropleth map that captures the relationship between protests occurrence at the municipal level in 2019, and the proportion of incumbent vote share for the 2020 presidential election.

This result is puzzling. The literature states that protests can point out grievances that otherwise could be concealed from the general population. It might be the case that the protests in Bolivia were so particular that the signaling mechanism did not operate. What sparked the protests were not complaints against the government per se, but rather claims of electoral fraud, where different sides (the pro-Morales side claiming that the election result was legitimate, versus the opposing side accusing electoral fraud) clashed over the legitimacy of the election. For future research, greater consideration has to be made regarding the cause driving the destabilizing protest cycle in order to assess in which cases these cycles can cause changes in electoral preferences.

Se souvenir d'Humoresques

Sous les temps de l'équateur

Du préjugé