Water governance as a common good

Selected as part of the ‘International Research Networks in the Humanities and Social Sciences’ programme, this project highlights new ways of governing water as a common resource. The network’s coordinator, Catherine Baron (LEREPS/Sciences Po Toulouse), explains its objectives and initial developments.

As part of an international research partnership, this project fosters interdisciplinary dialogue between researchers and civil society players who are collectively thinking about alternative water governance and development models in response to uncertainties arising from climate change and development trajectories. It is rooted in the international debates on water as a common good, and on the co-production and co-creation of knowledge. The aim is to respond to the limitations of participatory approaches, which fail to take into account power dynamics and the mandate for participation imposed by donors1. It reports on original research and methodologies co-developed by researchers, associations, and local populations in Southeast Asia, particularly in Thailand.

1. To initiate a debate with researchers and civil society players who, in Southeast Asia, are developing innovative frameworks for analysing the governance of water as a common resource and the co-creation of knowledge and management rules

2. To identify and document experiences in the co-creation of knowledge, illustrating representations of water as a common resource at the local level, in the context of intense pressure on water resources, and in connection with sustainable development strategies

3. To bring together a collective in order to respond to international calls for proposals on this issue, adopting a comparative perspective across Southeast Asia, France, and Africa.

The project is based on a number of findings identified from a literature review focusing on approaches to water as a common resource and on co-production in Southeast Asia. While some works focus on the governance of groundwater and the challenges related to sharing and preservation in the context of climate change, others examine the social and environmental impact of major infrastructure projects (such as dams in the Mekong Delta), from the perspective of transboundary water governance. In Thailand, these dams are primarily not used for irrigation but rather for electricity production, particularly to supply major urban centres. Publications on these issues highlight the geopolitical stakes, the power dynamics, and the socio-economic and environmental consequences of these political choices, referring to Political Ecology2 and the critical literature on the Commons3.

Original approaches in terms of commoning and co-creation of knowledge and rules were discussed during seminars organised with Thai universities

The first phase of the project involved identifying researchers and civil society players with critical perspectives on water governance in Southeast Asia. Original approaches in terms of commoning and co-creation of knowledge and rules were discussed during seminars organised with Thai universities4, with the support of the Fondation Maison des Sciences de l’Homme (FMSH) and the Research Institute on Contemporary Southeast Asia (IRASEC). Concrete and innovative experiments in the governance of water as a common resource were presented, taking into account the specificities of rural and urban contexts and territories in Thailand, Laos, Myanmar, and Indonesia. Some seminars led to the development of original organisational methods, testing out the deep dive workshop. This involved inviting local stakeholders to share their knowledge on water issues and engage in debating predefined and provisional questions, which were reformulated throughout the process.

This stage highlighted an original approach, Thai Baan Research, which serves as both an analytical framework and a methodology developed by Thai anthropologists5. It is a co-produced research process within collaborative research projects that go beyond traditional models of participation. Based on principles of social and environmental justice, governance rules for resources are jointly defined and discussed, and ‘embedded’ within local territories. The researcher is seen as a facilitator at certain stages of the process, acting as a mediator between locally organised groups and public policies. The villagers involved are referred to as ‘local researchers’. This approach, for example, is used to propose ‘counter-assessments’ to the social and environmental impact studies produced as part of major infrastructure projects (such as dams). They take into account the representations, knowledge, and skills of the local communities affected to draw up alternative impact studies with the support of researchers. The issue of institutionalising these alternative governance models and the role of the state in contexts where organised local collectives are marginalised remains open and extends the analyses of anthropologists (J. Scott6).

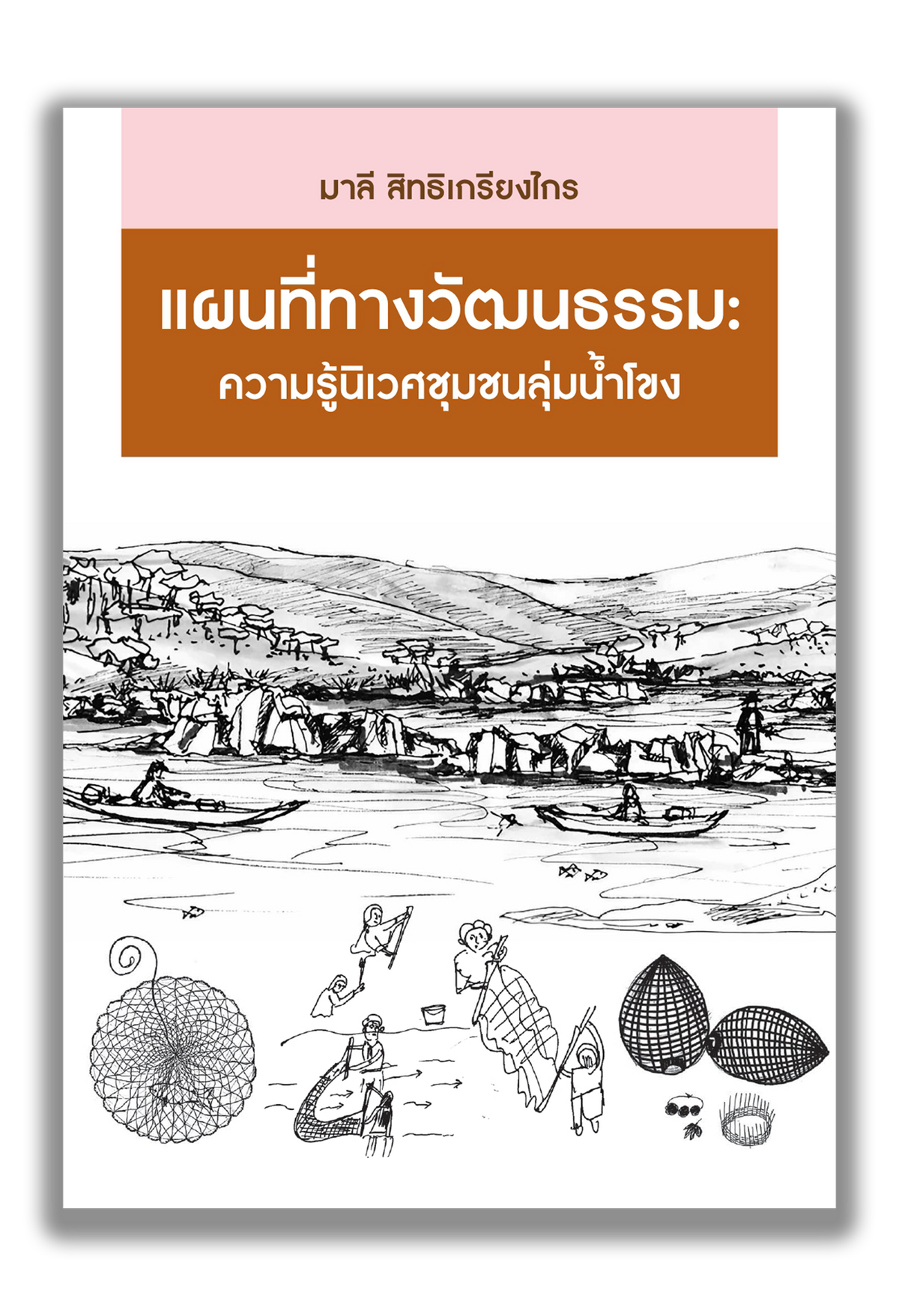

Cultural mapping : Local Ecological Knowledges on the Mekong River Basin

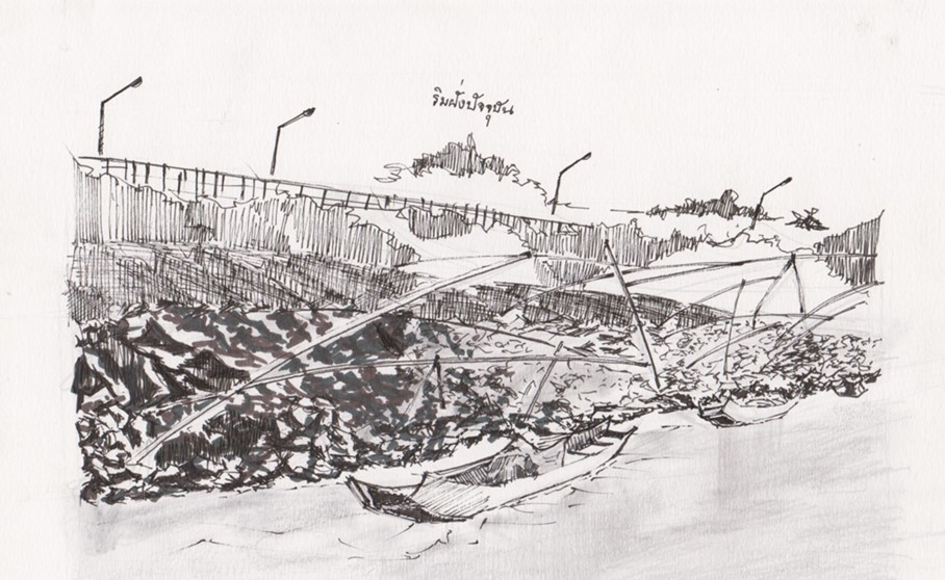

Écosystème des rives du Mékong à Ban Huay Luek, district de Waing Kaen, province de Chiang Rai

A variety of methodologies (participatory mapping, exhibitions of artistic creations, drawings, etc.) are experimented with based on contexts, to capture local knowledge and representations as closely as possible to the communities. Art is at the heart of these initiatives, because ‘far from being a simple representation or reproduction of the world as it is, artistic creation leads us to question and rethink the theories and mechanisms through which we represent the world.’7 The originality Thai Baan Research lies in considering the villagers as artists capable of expressing their sensitive relationships with water. A publication (edited by the CESD, Chiang Mai University) presents these artistic creations and explains the relationship between the villagers and their environment, including both humans and ‘other-than-humans’8.

It makes visible other ways of relating to the world, and to water in particular, and rehabilitates epistemologies considered minor by dominant knowledge and power structures.

But beyond innovative methodological tools, this research is contributing to international debates on ‘Epistemologies of the South’9, and to the construction of an alternative, decolonial way of thinking about ‘development’10. It makes visible other ways of relating to the world, and to water in particular, and rehabilitates epistemologies considered minor by dominant knowledge and power structures. While decolonial thinking is often associated with South American research, this project highlights work from other geographic areas (such as Southeast Asia)11.

The second phase of the project will involve participant observation of co-creation processes, supporting Thai socio-anthropologists in their fieldwork with communities in northern Thailand and the Isan region. Additionally, identifying original experiences of co-creation, such as those in The Mekong Schools12, will enable us to explore certain local innovations in greater detail.

Meetings with South American and African researchers would provide an opportunity to compare common and unique histories and encourage South-South partnerships on these issues.

While these approaches are shared and discussed within the sub-region, they remain largely under- debated beyond that. Meetings with South American and African researchers would provide an opportunity to compare common and unique histories and encourage South-South partnerships on these issues.

Article published in the second issue of the Journal de la FMSH.

Footnotes and bibliographical references:

1. Frances Cleaver, ‘Paradoxes of Participation: Questioning Participatory Approaches to Development’, Journal of International Development 11, no. 4 (1999): pp. 597–612.

2. Alex Loftus, ‘Political Ecology I: Where is Political Ecology?’, Progress in Human Geography 43, no. 1 (2019): pp. 172–182.

3. Pierre Dardot and Christian Laval, Commun. Essai sur la révolution au XXIe siècle (Paris: La Découverte, 2015).

4. The Center for Social Development Studies (CSDS), Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok; The Regional Center for Social Science and Sustainable Development (RCSD) and The Center for Ethnic Studies and Development (CESD), Chiang Mai University; Mae Fah Luang University, Chiang Rai; Ubon Ratchathani University.

5. The representative figure is Professor Chayan Vaddhanaphuti (RCSD), in collaboration with Malee Sitthikriengkrai (CESD). Alexandra Heis and Chayan VADDHANAPHUTI, ‘Thai Baan Methodology and Transdisciplinarity as Collaborative Research Practices: Common Ground and Divergent Directions’, ASEAS 13, no. 2 (2020): pp. 211–228.

6. James C. Scott, The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia (New Haven: Yale UP, 2009).

7. See the FMSH call for proposals, Arts and HSS, https://www.fmsh.fr/en/funding/arts-hss.

8. We use the term ‘other-than-human’ rather than ‘non-human’, which defines a default category. This makes it possible to consider agency from both human and non-human sources, including living and non-living entities.

9. Santos Boaventura De Sousa, Epistemologies of the South: Justice Against Epistemicide (New York: Routledge, 2014)

10. Philippe Colin and Lissell Quiroz, Pensées décoloniales. Une introduction aux théories critiques d'Amérique latine (Paris: La Découverte, 2023).

11. A conference, ‘Decolonization of Southeast Asian Studies’, will be held in Chiang Mai from 17 to 19 July 2025.

12. The Mekong Schools in Ta Mui (Ubon Ratchathani Province) and Chiang Khong (Chiang Rai Province).

Plastiques et Océan : comprendre une crise globale

Sous les temps de l'équateur. Une histoire ancienne de l'Amazonie centrale

Le coopérisme