Electoral Democracy in Danger?

This text follows the presentation of the paper “Let’s (Not) Disagree: How Tolerance for Disagreement Shapes Horizontal Affective Polarization”, at the Summer School “Electoral Democracy in Danger?”, organized at Sciences Po Paris, 3-7 July 2023

Engagement between fellow citizens who have opposing political views are becoming increasingly adversarial. Coined as “Affective Polarization”, this development has alarmed scholars and the wider public alike. Nonetheless, disagreement and conflict are also central tenets of both everyday interpersonal relationships and democratic life. However, the way people experience and cope with disagreement can differ substantially as it encompasses an interplay of one’s innate personality and social norms. We aimed at understanding the political disagreement and conflict that has arisen from the worryingly levels of polarization by diving into factors that cause, and potentially reduce, polarized perspectives. We hence hope to offer fresh insights and actionable solutions.

Affective Polarization (AP) – the trend where individuals view political opponents negatively and political proponents positively – is a growing concern. Rather than being confined to mere ideological disagreements, this polarization has seeped into our emotions and daily interactions. Recent events, like the Capitol Hill insurrection and the deep societal rifts exposed by the Brexit referendum, highlight the urgency to understand and address AP.

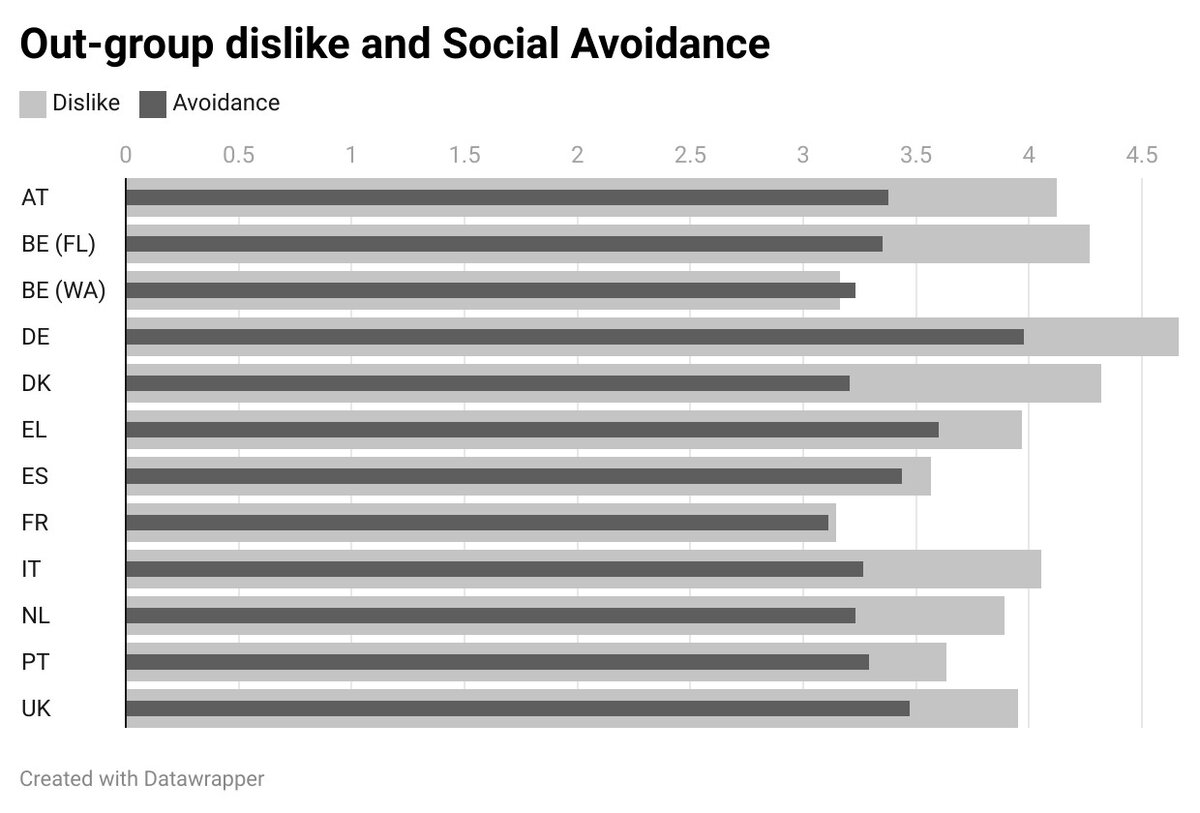

We can identify two main levels at which affective polarization happens: the attitudinal and behavioral one. These can be observed by examining both people’s intended socially avoidance behavior towards out-partisans and their level of dislike. Figure 1 shows that the intensity of the two levels is indeed different across contexts. Overall, people tend to exhibit more out-group dislike than avoidance.

Moreover, the study differentiates between horizontal polarization (negative feelings among ordinary citizens towards those with opposing views) and vertical polarization (negative feelings towards political parties). From previous research, we known that most citizens harbor more animosity towards political parties than their co-citizens. As we will show, these two types of polarization should not be used interchangeably, as they tap different underlying dimensions.

Figure 1: aversion pour les groupes extérieurs et évitement social dans les différents pays (scores moyens).

Previous research on affective polarization has predominantly focused on common political factors, such as partisanship, ideological differences, and political interest. Yet, some interesting insights in how personality shapes affective polarization have also been conducted. At the heart of our research, and arguably its most compelling proposition, is the introduction of a concept known as "Tolerance for Disagreement" (TfD). TfD is a personality trait (influenced by societal norms) which dictates how one perceives and copes with interpersonal conflict. Unlike the commonly held perception where disagreement is seen as a confrontation or a threat, individuals with high TfD perceive it as a natural, or even constructive, part of human interaction. We expect that people whose threshold for interpersonal conflict is higher will have stronger coping mechanisms to deal with different viewpoints, and hence exhibit lower levels of AP. Importantly, we only expect to find this for horizontal AP, as our mechanism clearly operates between citizens, not between citizens and the elite. Our data shows that average levels of TfD are highly similar across countries, with the exception for Belgium and the United Kingdom for which it is significantly lower.

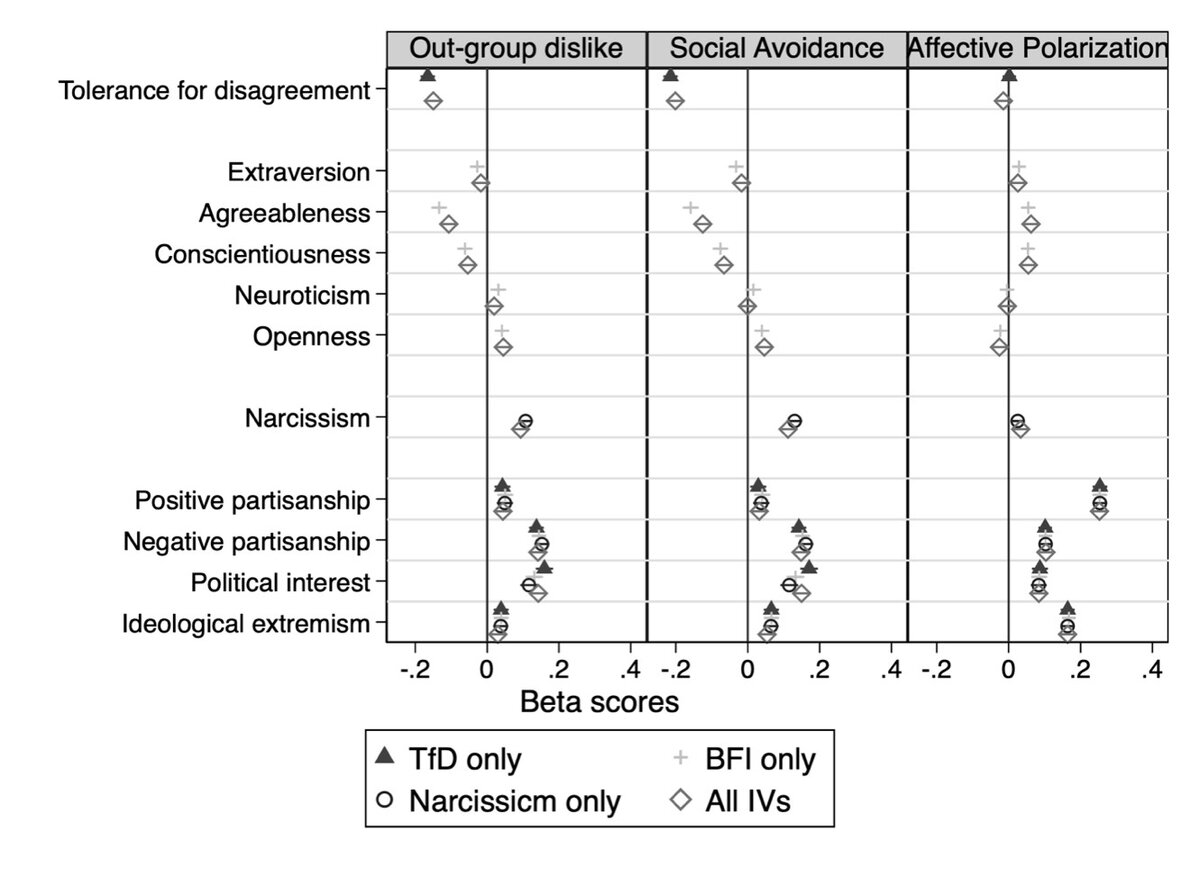

Harnessing data from a vast sample across eleven West-European countries and twelve political systems (N = 12,000), the research assessed the impact of TfD and other personality traits (Big Five and Narcissism) on AP. Several findings can be highlighted, displayed in Figure 2. The standout discovery was the predictive power of TfD. However, there is a clear difference between how individuals perceive voters versus parties. While TfD played a major role in the horizontal dimension, it was indeed absent in the vertical dimension. Nonetheless, it emerged as a dominant predictor of horizontal AP, underscoring its importance. Its significance even held when including personality traits. The effect sizes of these personality traits are much smaller in comparison to TfD. This is not to say that other traits played no role at all. Narcissism, for instance, consistently influenced AP across both dimensions. In contrast, Agreeableness, reflecting one’s degree of cooperativeness and trust, leads to less out-group dislike and social avoidance. Interestingly, extraversion (one’s tendency to be outgoing and socially engaged), which was found highly significant in previous research, became insignificant when including TfD, suggesting that they tap into similar dimensions.

Extraverted people might hence be more inclined to seek out new connections, which others have stated should reduce AP, but if they exhibit low levels of TfD, this relationship probably does not hold. This find further highlighted that TfD is a powerful predictor of whether an individual would avoid or dislike a fellow citizen based on differing political beliefs.

Figure 2 : scores bêta pour l'aversion pour les groupes extérieurs, l'évitement social et le score de dispersion pondéré de la polarisation affective.

These findings bring forth two primary implications. Firstly, they highlight the need for future research to understand the nuanced differences between the reasons we harbor negative feelings. One cannot assume uniformity in the causes or manifestations of AP. As we showed, the causes of dislike towards fellow citizens (horizontal) might be very different from those aimed at political parties (vertical). Future research must be wary of distinguishing these two dimensions. Second, and perhaps more pertinently for society at large, is the emphasis on awareness of one’s TfD. If the goal is to weave a societal fabric where diverse views can coexist and complement, being aware of Tolerance for Disagreement and offering tools to learn how to cope with different political viewpoints seems like a viable path forward. While this might not dissolve deeply entrenched views on political systems, it can foster an environment of understanding and healthier democratic dialogue.

In conclusion, as affective polarization continues to influence our societies and relationships, understanding the factors driving it is of paramount importance. Our study offers a fresh perspective, emphasizing the importance of individual traits and their interplay with societal norms. While the journey to a more cohesive society might be long and complex, raising awareness of how our own tolerance for disagreement shapes our relation to different political viewpoints might be a significant step in the right direction.

This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant agreement no. 759736). This publication reflects the authors’ views and that the Agency is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains.

Sous les temps de l'équateur. Une histoire ancienne de l'Amazonie centrale

Le coopérisme

De la rue à la mairie