Disruption or Erosion? Patterns of Democratic Regression over Time

This text follows the presentation of the paper “Typologizing processes of autocratization: How to integrate time, outcome, and context?” at the Summer School “Electoral Democracy in Danger?”, organized by the CÉRIUM-FMSH Chair on Global Governance, Paris, 3-7 July 2023

In recent years, there seems to be a broad consensus on how democracies die nowadays: First, they do not decline by coincidence, but because of deliberate actions of political actors. Second, this rarely happens overnight, but mostly in the form of gradual processes. When describing these two progression forms, we normally fall back on supposedly archetypical examples, with military coups in Latin America in the 1970s representing disruptive forms and the episodes of Hungary under Orbán or Venezuela under Chávez being paradigmatic for democratic erosion.

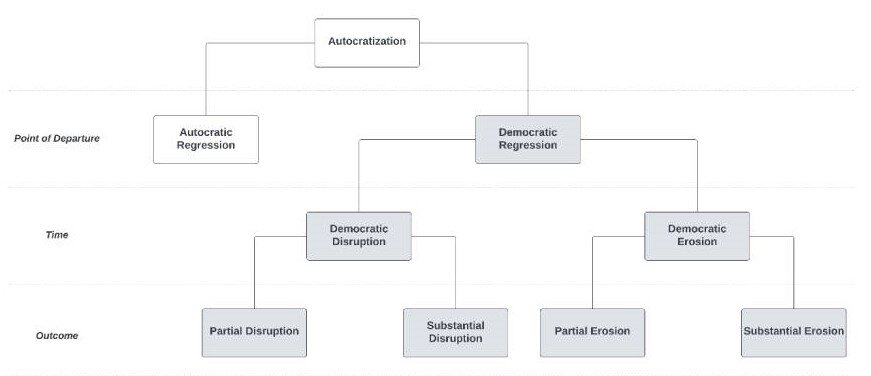

Using Data from the Episodes of Regime Transformation Dataset (ERT) I show that episodes of democratic regression that last longer than a usual election period (> 5 years) differ significantly in their progression form from those that end earlier (≤ 5 years). I classify the former as democratic erosion, and the latter as democratic disruption. Going on I refer to a three-dimensional conceptualization of autocratization considering the point of departure (democracy/no democracy), duration, and outcome (regime change/no regime change) for comparative analyses. The findings indicate that claims of a change in the nature of democratic regression often fall short, as we can observe a diversification of progression rather than a uniform change from one archetype to the other after 1989.

Figure 1: A three-dimensional Conceptualization of Autocratization

We still lack established criteria and thresholds for differentiating episodes of rather rapid (disruption) and rather gradual (erosion) declines of democratic quality. I argue that it should be possible to represent courses of democratic regressions in terms of time/duration and decline rates. This leads us to how we can define meaningful thresholds of these parameters.

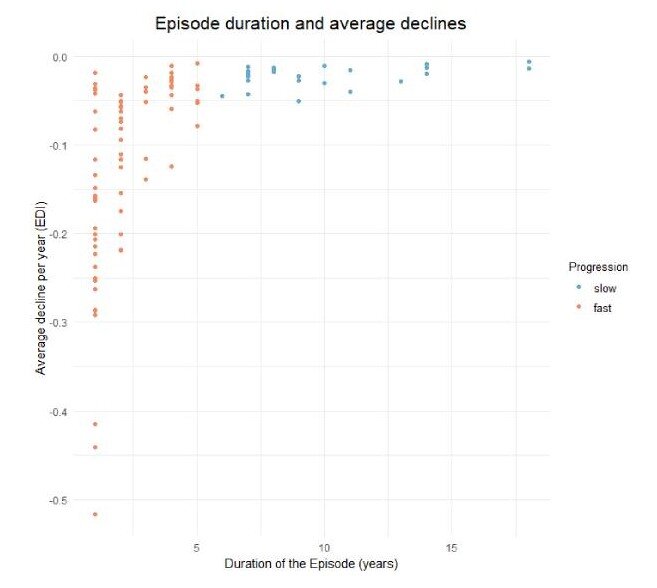

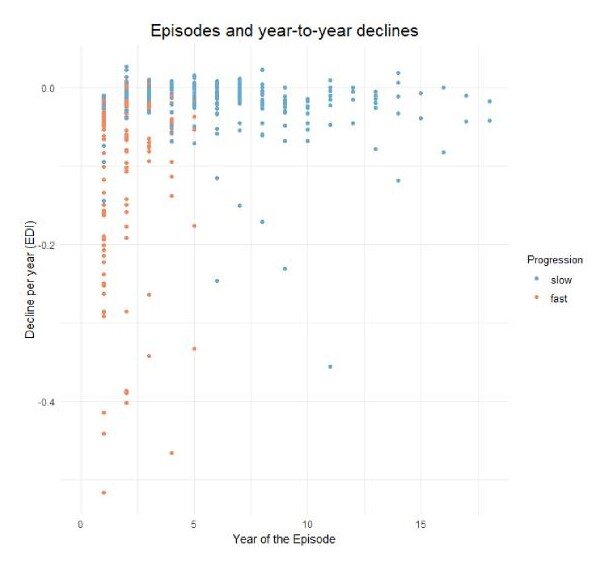

One way to make progress on this is an explorative data analysis. Consequently, I tested thresholds of duration from 1 to 10 years. None of these cut-off points helps to generate two considerably homogenous groups of episodes regarding their decline rates, as standard deviations remain high. However, we can observe that the standard deviations for decline rates in both groups are the lowest when we use duration > 5 years as the threshold. Plotting the average decline rates (Figure 2) and year-to-year declines (Figure 3) clearly underlines this finding and indicates the meaningfulness of this threshold as a first anchor to differentiate rather disruptive/fast and rather gradual/slow episodes of democratic regression.

Figure 2: Episode duration and average declines

Figure 3: Episodes and year-to-year declines

How can we make sense of this pattern? I start from the observation that accountability mechanisms are often crucial to democratic resilience. It is plausible to assume that autocratizers know this as well. The fact that they often start their project by undermining the independence of courts, the possibilities of parliamentary control, and the fairness of elections also speak for this. The kind of accountability mechanism we find in virtually every democracy, and perhaps the ultimate lever against anti-democratic governments (see e.g. Czechia, Slovenia), is democratic elections.

I assume that autocratizers take this into account in their strategic calculations and thus have two basic paths of action to choose from: Either they change the rules of the game abruptly and bet on the fact that they succeed in a short period. This way there will be no more sufficiently free and fair elections that could separate them from power again in time. Or they take a more patient and subtle approach, making it harder for citizens and the opposition to clearly identify and mobilize against anti-democratic behavior (see e.g., autocratic legalism, stealth authoritarianism).

By combining this anchor with the Regimes of the World (RoW) framework, it is possible to operationalize the three-dimensional conceptualization of autocratization. Based on that I identify 94 episodes of democratic regression since 1900. 69 (73 percent) are classified as rather fast ones (disruption), whereas 25 episodes represent slow progression forms (erosion). While 73 episodes (78 percent) resulted in a regime change, six episodes ended before that. A further 15 episodes are still ongoing and therefore neither evaluable regarding their outcome nor classifiable regarding the four subtypes of democratic regression (see Figure 1). As a result, I identified 64 episodes of substantial disruption, two of partial disruption, four of partial erosion, and eleven of substantial erosion.

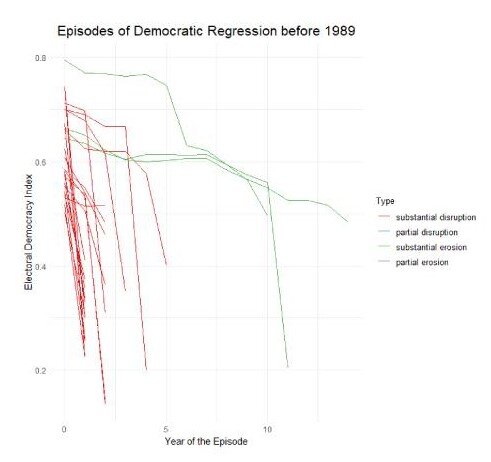

Figure 4: Episodes of Democratic Regression before 1989

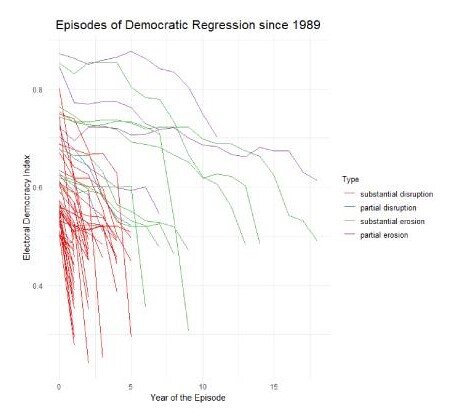

Against the background of these findings, what can we say about claims of democratic regression changing its nature? I choose the turning years of 1989/90 as the dividing line for a diachronous comparison, as this is often considered a critical juncture in democracy research and the peak of the so-called ‘third wave of democratization’. Looking at the plots (Figure 4 and 5) I argue that there is some evidence for the emergence of formerly rather unusual forms of democratic regression (erosion). However, do fast forms of democratic regression completely belong to the past? This is not the case at all. Both partial disruptions identified took place only recently in Lesotho (2015-2017) and Moldova (2013-2017). In addition, more than half of all substantial disruptions fall into the period since 1989. Consequently, we must note that democratic regressions occur today in various forms featuring rather disruptive or rather gradual characteristics. Thus, we cannot speak of a complete shift from an old to a new archetype, but of a diversification of courses of democratic regression.

Figure 5: Episodes of Democratic Regression since 1989

In this blog post, I presented a framework for how to systematically differentiate episodes of democratic regression considering time and outcome. In the descriptive analysis, I pointed to an initial anchor for differentiating between rather disruptive and rather gradual progression forms. Furthermore, I found evidence that we should not speak of a complete shift regarding the nature of democratic regression, but rather of its diversification after the peak of the third wave of democratization. I conclude that the framework used here can help to better systemize research on the causal explanation of democratic regression. This can be achieved, for example, by basing the case selection for comparative studies on the three dimensional conceptualization of autocratization.