Interview with Laura Nys | Herman Diederiks Laureate 2020

In 2020, Laura Nys was awarded the Herman Diederiks Prize for her article "Distance and proximity. Interpersonal relations between pupils and educators in the Belgian reform school of Mol (1927-1960)". In this interview, she tells us more about her research process and explains how the prize has impacted her academic carreer.

- Could you tell us about your studies and your home institution?

I obtained my PhD in January 2020. During my PhD research, I was working at the history department of Ghent University and the criminology department of the Vrije Universiteit Brussels. Working at two departments in two disciplines is something that I can recommend to everyone. Ghent University really feels like my home institution: I graduated there and I am first and foremost a historian. My co-supervisor then introduced me to criminology department of the VUB. Listening to the research experience of colleagues in the field of criminology enriched my knowledge considerably. Of course, as a historian I am working with completely different methods and sources than colleagues who are for instance conducting field work in prisons, but their research made me look at my sources with fresh eyes. They recommended me literature that I would never have read otherwise. My supervisors, Gita Deneckere and Jenneke Christiaens, have always been very supportive, as was also the case for my advisory board. In March 2020, I started working at the Hankuk University of Foreign Studies in Seoul, my current home institution.

- What was the subject of your thesis/awarded research?

My PhD thesis looks at the role of emotions in Belgian reform schools between 1890 and 1960. In my dissertation, I try to bridge criminal justice history and the history of emotions. The first discipline has a great expertise in bringing to the surface the voices of underprivileged groups, whereas the second, in considering emotions as historically and culturally variable, asks new and intriguing questions that can shed light on detainees’ experiences. My dissertation looks at emotions in three ways. First, I discuss the role of emotions in emerging scientific practices in the reform schools, such as the psychological observations. Second, I look at the encounters between staff members and detainees. Third, I focus on the ego-documents written by the detainees themselves, giving us insight in their detainment experience, but also highlighting the potential for agency and resistance against the emotional rules that they had to abide by.

The article that I submitted for the Prize deals with interactions between staff members and detainees. I argue that we have to acknowledge the violent nature of carceral relations, but that alongside coercive practices, there was a wider array of social interactions. Ego-documents from both pupils and educators provide insight into these micro-interactions, the emotions and the power relations involved

- In what context have you decided to apply for the Herman Diederiks Prize?

In general, I like the fact that CHS is a bilingual journal and that it has an open access policy. Regardless of the Prize, I wanted to try to submit an article for CHS. While I was working on my PhD, I did not always see clearly how the pieces fitted together. Having all the chapters connected, enabled me to write this article. This felt like the right timing. I felt also encouraged by my jury and advisory board to communicate my research.

- How could the Herman Diederiks Prize impact your research?

I feel very grateful to have received this Prize. It is a fantastic encouragement. As a researcher, I am often plagued by doubts: is my research really good enough? The fact that the editorial board awarded me this prize, means a lot to me. The funding enables me to continue my research and to publish more. Everyone thinks of course that their research is important. There are so many interesting intellectual developments! Nevertheless, I genuinely think that the combination of the history of emotions and historical criminology is an interesting road to explore in more depth.

- Has the difficult context of 2020 led to a change in your research methods?

Working remotely cuts us off from our colleagues. Of course we can e-mail or zoom, but it is often these unplanned encounters in the coffee room or at the copy machine, that lead to spontaneous exchanges of book tips, ideas, questions, … Talking to colleagues gives so much inspiration and energy. I need time alone to think and write, but I also need these informal energising talks. One can question whether this is really a “research method” strictly speaking. Yet, sharing knowledge and working together is integral part of any research process and it deserves more acknowledgment, in my view.

I left Europe in February 2020 to start my new job in Seoul. I knew that I would be living on the other side of the world, but back then I was fully convinced that I would be back in summer to consult the archives. Of course, that has not happened. I have not left South Korea since I arrived, and I will probably visit Belgium only in the winter of 2021/2022. The pandemic requires us to rethink practices that we always took for granted, such as long-distance travelling. It is challenging, but sometimes it is good to question habits that we always considered as normal. I imagine that for scholars relying on field work, especially with vulnerable groups, the impact of the pandemic on their research method is much bigger and will last longer than for archival work – not to mention the impact of the pandemic on all other domains of society of course, aside from research.

- What is the next step in your academic career?

As of March 2020, I am working at the Department of Dutch at the Hankuk University of Foreign Studies in Seoul. Teaching to Korean students is so rewarding: their questions force me continuously to rethink my own position as a Belgian scholar. What I would like to give them, is my view on history. I really take effort to include the history of everyday life in my course: the history of the bicycle for example. Or the history of the supermarket. This is not always what they expect, but it ís our history too. So far, I have only met my students online. Even the digital encounters are great, but I cannot wait to meet them in real live, to see their faces and to hear their excited sighs when they understand something new.

Laura Nys

Hankuk University of Foreign Studies

pictures

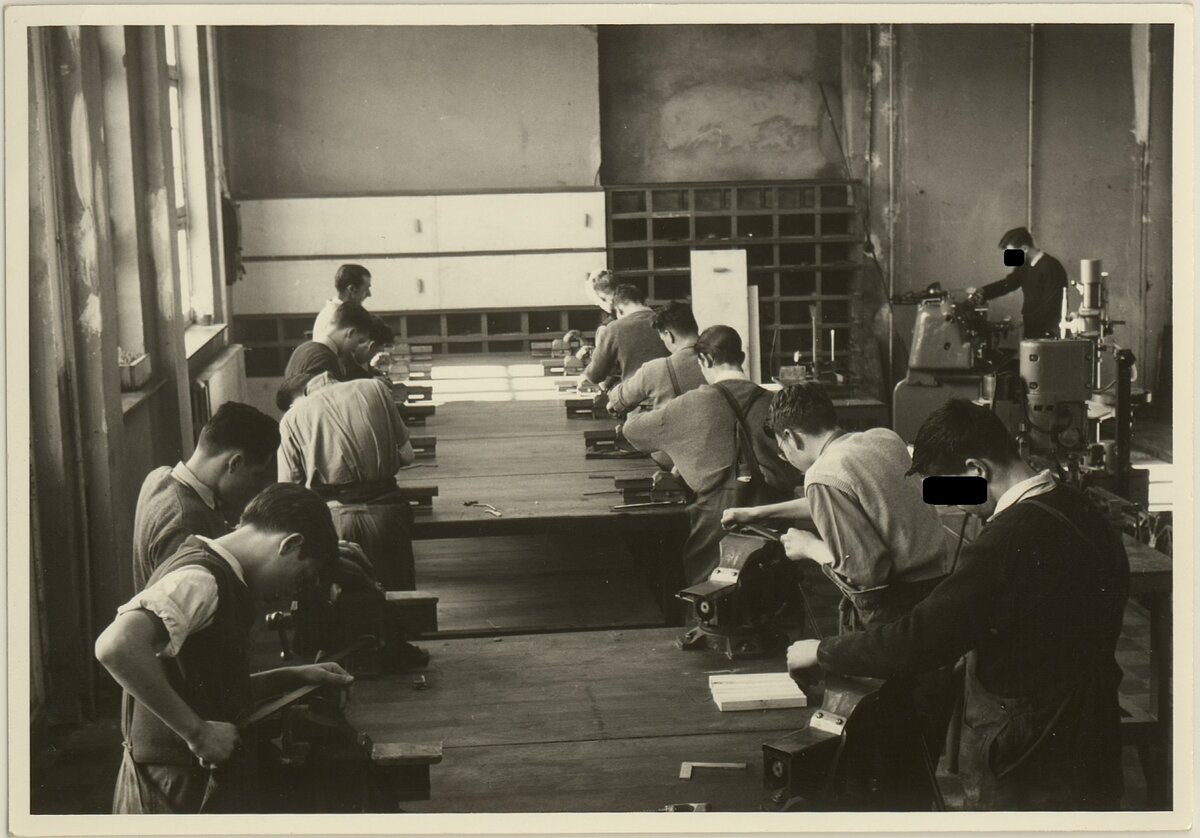

The State Reformatory of Mol, ca. 1920-1949

Vocational training in the Central Observation Institute of Mol (“De Hutten”), ca. 1920-1949.

(anonymised) personal case file of a girl detained in the reform school of Bruges, ca. 1893.

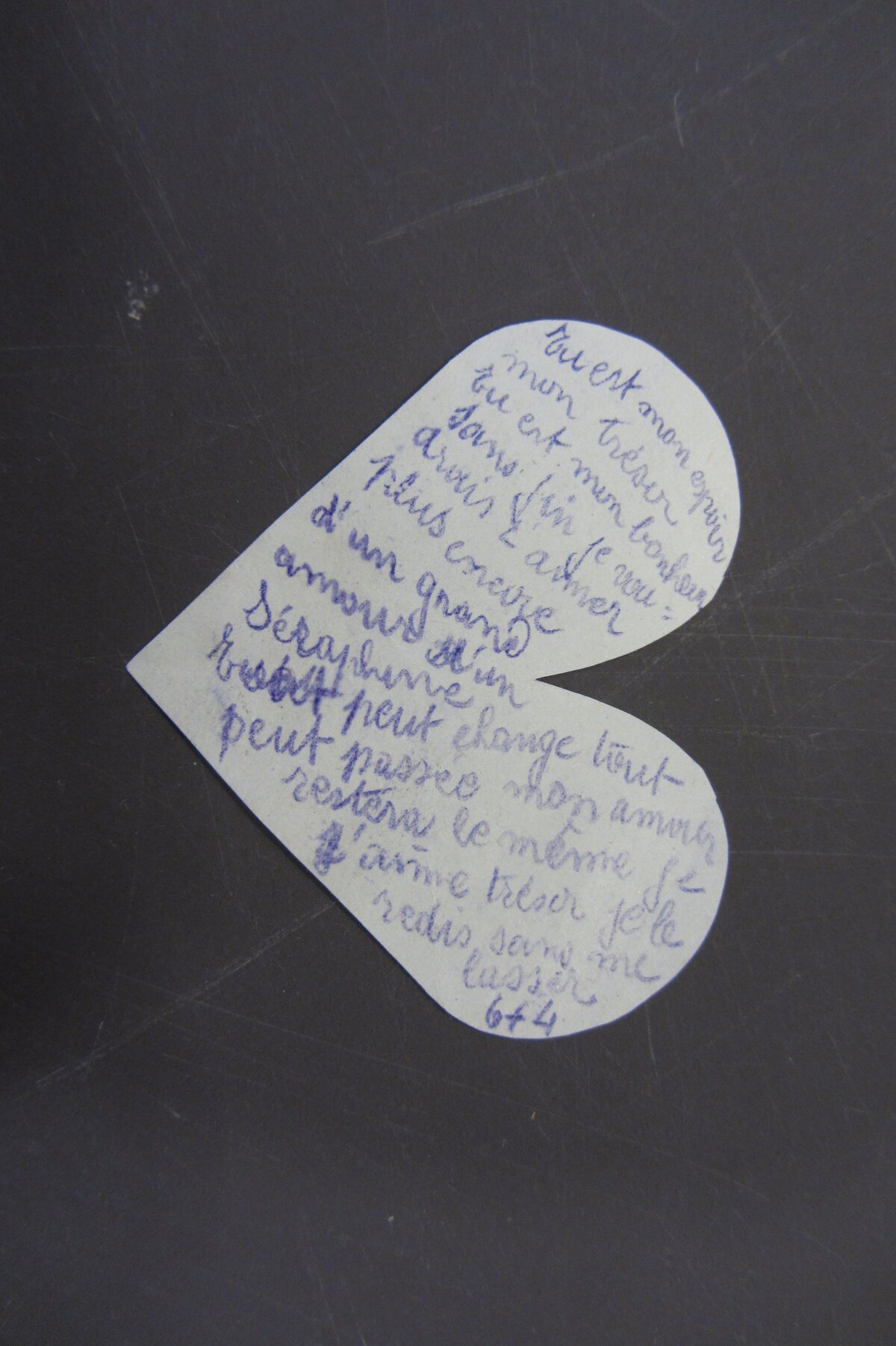

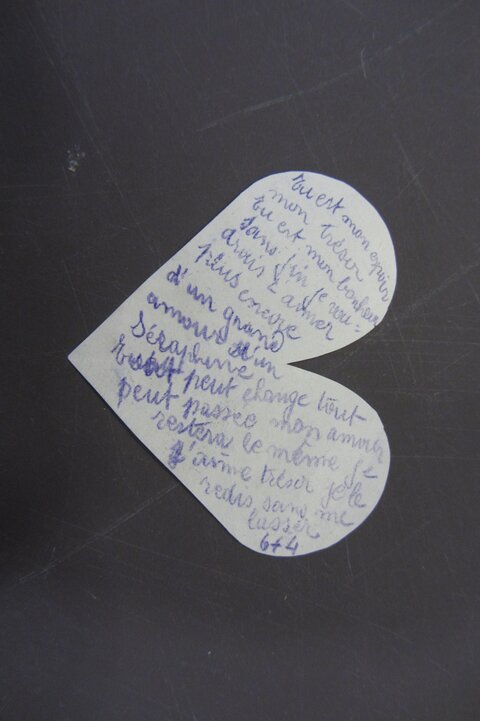

Clandestine letter of a detained girl in the State Reformatory of Bruges, ca. 1930

Index de l'égalité professionnelle 2025

FMSH and the Social Science Research Council Lay the Foundation for International Cooperation

#Restitutions. Another Definition of the World