Vegetation and urban living in cities in the ‘Global South’

2023 winning project of the "International Networks in HSS - Climate and Environment" programme, the “Plants in southern cities” network analyzes the informal appropriation of public spaces in response to an under-provision of green spaces by the public authorities. Its coordinator, Aude Nuscia Taïbi (Université d'Angers), tells us more about this network.

Urban vegetation refers to the sum of all public and private green spaces within or on the perimeter of urban areas, including managed land, wasteland, and spontaneous vegetation, and comprises plant communities of all sizes as well as individual plants. Plants in urban areas provide numerous ecosystem services, or benefits, to residents, particularly in terms of temperature regulation and controlling air and rainwater pollution. These services are crucial within the context of climate change and the rise of extreme weather events, such as heatwaves and heavy rainfall, which can have damaging effects on cities composed largely of mineralised and impermeable surfaces. Urban vegetation also provides social and cultural services, generating benefits in terms of recreation, aesthetics, landscaping, and well-being, as well as economic services, which help to reduce the negative effects of urbanisation and high population density on quality of life and the environment. For all of these reasons, urban vegetation is widely integrated into public policy in countries in the ‘Global North’, even if the practical disservices of such vegetation are sometimes overlooked. In Europe, urban vegetation has been part of urban policy since the nineteenth century, on the basis of hygienist theories which found fresh impetus in the early 2000s with the development of a more sustainable form of urban planning, concerned with the environment and limiting urban sprawl.

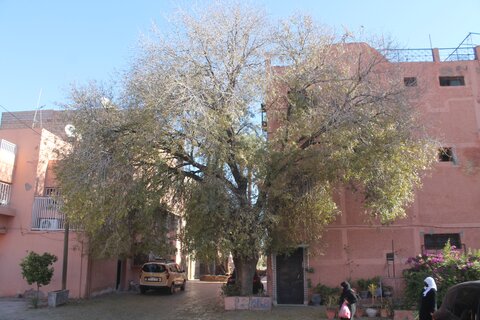

Trottoir végétalisé, Quartier Syba Marrakech, 2022

Trottoir végétal à Daoudiat, Marrakech

Quartier Daoudiate Marrakech, 2020

Urban vegetation is, however, not a major concern in cities in the ‘Global South’, despite the fact that issues relating to the environment, quality of life, and the ecosystem services of urban vegetation are perhaps of greater consequence in these cities—which are often hot, polluted, and stressful, with poorly managed urban growth, and higher rates of poverty—than in Western cities where such policy is more prevalent. Granted, these concerns may not have seemed a high priority for African decision-makers in the years following independence (1950–1970), given the otherwise pressing difficulties of managing development, food, housing, access to drinking water, and urban growth.

This situation is largely explained by the specific context of colonisation. The majority of public green spaces in African cities date back to the colonial period, when urban vegetation was introduced for landscaping, social, aesthetic, health, and even security purposes. These spaces played a role in colonial urban planning and its drive to dominate and exclude the ‘natives’. In French-speaking Africa, colonialism produced dual cities, where colonial vegetation became part of a wider strategy of controlling spaces and populations.

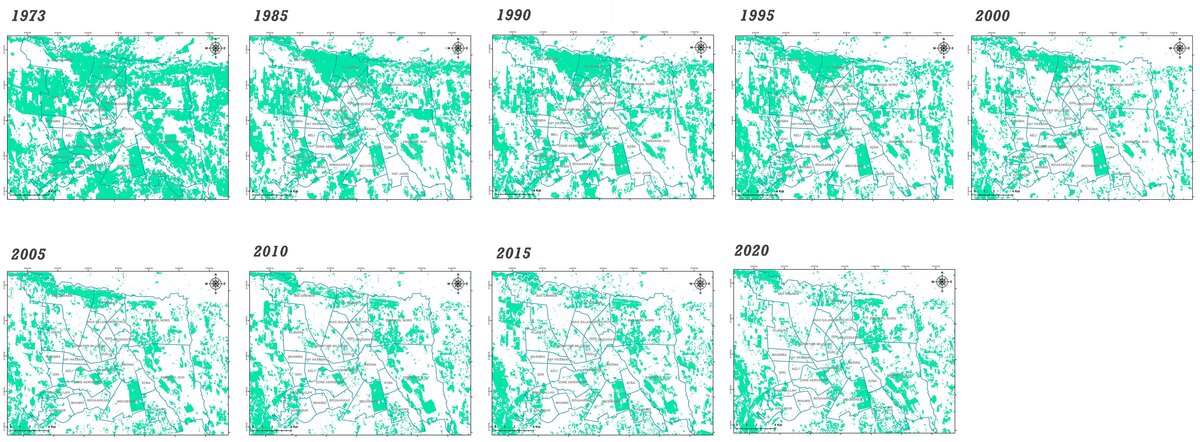

Le recul du couvert végétal dans la Communauté Urbaine de Marrakech de 1973 à 2020.

In the years following independence up to the end of the 1990s, few new public green spaces were created in African cities, and those left over from the colonial period, which made up the bulk of the public parks and gardens accessible to residents, were neglected and degraded. Renewed interest in public green spaces began to emerge in the 2000s, with the rehabilitation of certain colonial parks and gardens, and improved efforts in urban policy to introduce new green spaces, even if this was often done as an afterthought. This development echoed a growing demand for nature in cities, both in Africa and throughout the rest of the world. However, the provision of public green spaces remains insufficient in most African cities—often well below the 10 m2 of green space per inhabitant recommended by the WHO—and the distribution of this space is still highly unequal, even as social demand has grown steadily alongside urbanisation.

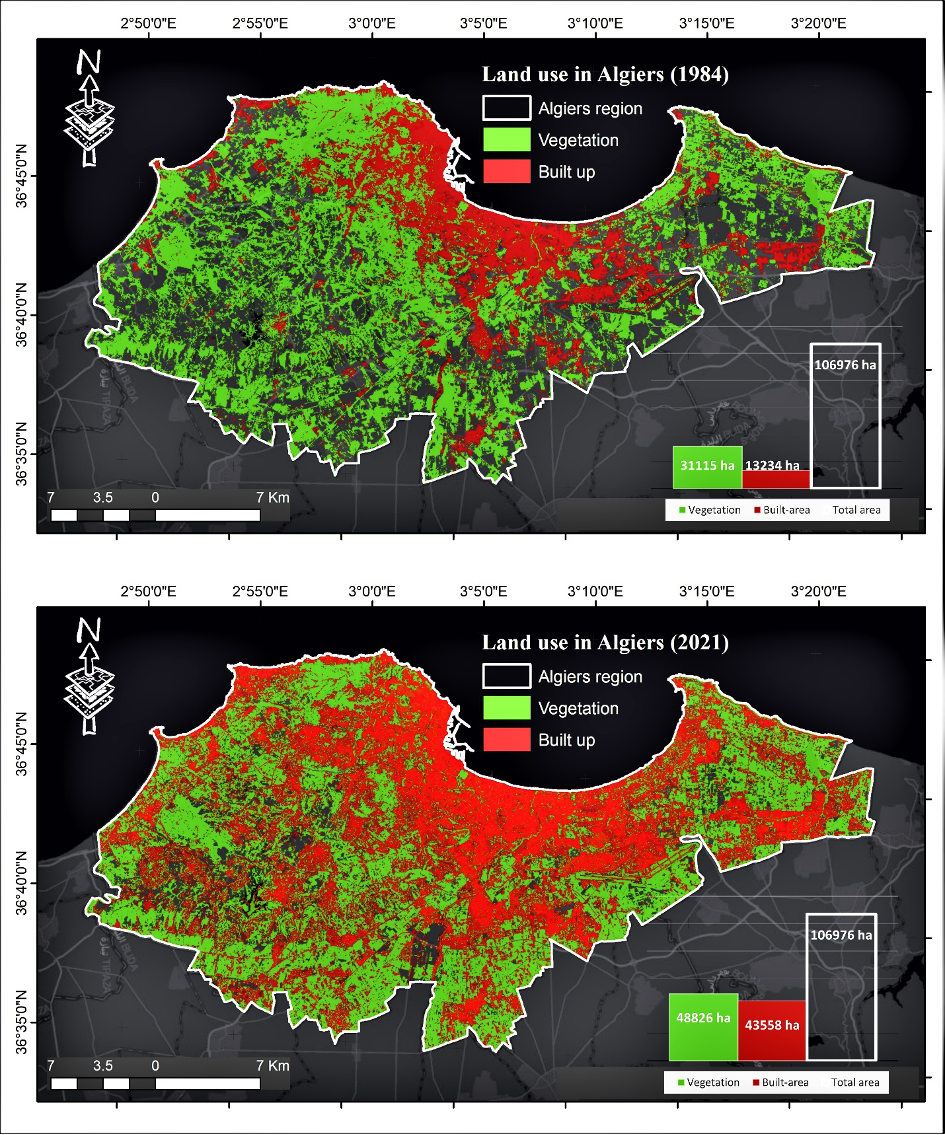

Croissance urbaine d'Alger de 1984 à 2021

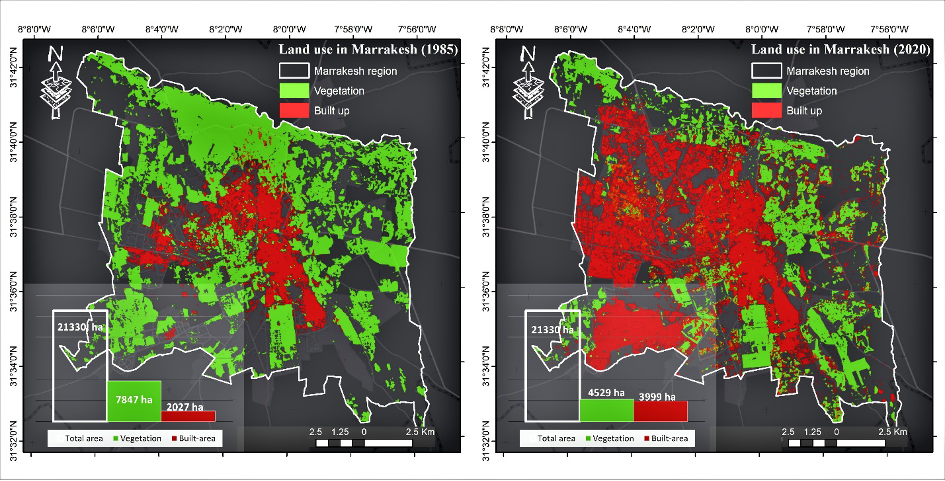

La croissance urbaine à Marrakech de 1985 à 2020

La croissance urbaine à Sousse de 1984 à 2021

In view of this shortage, and the inability of the authorities to meet the needs of those living in cities, an informal social movement to revegetate pavements has developed in most North African and sub-Saharan African cities over the last few decades. Very different from the revegetation practices used for high-end property developments, such as villas, this phenomenon involves the informal appropriation of public spaces, such as pavements, by residents. The movement is indicative of an evolution in the approach to and management of nature in cities. The latter [MB1] were, in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, primarily the domain of public authorities. However, since the end of the 1990s, they have been increasingly dominated by the general public, with residents keen to participate towards shaping their living environments, having been previously confined to private spaces. While ecological concerns do not appear to be the driving force behind these changes, they can be likened to a sort of environmental activism, or a form of individual socio-environmental protest and mobilisation. Above all, this shift hints at a loosening of control over the public space by the authorities, which are willing to tolerate private transgressions as long as they remain within the limits of acceptability, even if these actions often create real obstacles to mobility.

Article published in the second issue of the Journal de la FMSH.

Sous les temps de l'équateur. Une histoire ancienne de l'Amazonie centrale

Le coopérisme

De la rue à la mairie