“Mexico: A land of the disappeared”

The result of an original and unprecedented collaboration between a research team, photographers, an international solidarity group against state violence, and the FMSH, the mook aims to offer a new way of telling the story of a human tragedy and its conjurations. By giving a voice and a face to the families of victims who follow the traces of their loved ones, the accounts and photographs in this work provide keys to understanding how a society lives in, with, against, and after extreme and massive violence. The anthropologist Sabrina Melenotte offers explanations.

The phenomenon of disappearances in Mexico: The state of play in 2023

On 26 September 2023, Mexican society commemorated the ninth anniversary of the disappearance of forty-three students from Ayotzinapa, under conditions that have now been clarified thanks to the work of critical journalists and above all the Interdisciplinary Group of Independent Experts (GIEI). The latter has carried out in-depth work demonstrating the role of the army in suppressing or fabricating evidence, and the collusion between members of the Guerreros Unidos cartel, the municipal president, and the municipal police of Iguala and the surrounding towns.

To date, 111,642 people have disappeared in Mexico since 1962, the vast majority since 2006—almost four times as many as during past Latin American dictatorships in the Southern Cone. In addition, there have been an estimated 432,000 murders in Mexico since 2006[MB1] . These worrying figures must be viewed in the context of the "war against drug trafficking" launched in 2006 by former president Felipe Calderón Hinojosa and which continues to this day. This war has led to the militarisation of the public sphere and the daily lives of Mexicans, with a drastic increase in homicides, femicides, disappearances, extrajudicial executions, and massacres across the country.

This situation of extreme and massive violence casts a dark shadow over the security policies that have been in place for seventeen years now, which have not only proved ineffective, but have also exacerbated the insecurity of Mexicans and human rights violations in the country. Before 2006, specific sectors of the population—activists, students, guerrillas, or simply organised peasant or indigenous groups—were the first to be affected by disappearances. After 2006, disappearances became widespread and extended to the entire population, even though they continued to primarily affect the most vulnerable groups (the poor, women, indigenous people, migrants, journalists, social and environmental activists, human rights defenders, etc.).

The cruel treatment of corpses, which are disposed of by any means necessary in order to conceal the crime, reflects the devaluation of death.

The term “disappearance” thus covers a wide range of violent situations, making their analysis complicated and warning us against hasty generalisations. It is now difficult to say precisely why people are disappearing, since investigations are making little or no progress, impunity reigns supreme, and the official discourse has been undermined since the “historical truth” in the Ayotzinapa case turned out to be a series of lies and concealments of evidence. However, whatever the motive, the mass disappearances reflect above all the devaluation of life in Mexico, where it is easier to make someone disappear than to settle a conflict peacefully. Similarly, the cruel treatment of corpses, which are disposed of by any means necessary in order to conceal the crime, reflects the devaluation of death. And these lives and deaths that do not count are directly linked to the impunity that prevails in the country.

I have borrowed the term necropolitics from Achille Mbembe to talk about a power that produces violence and mass death. In Mexico, this power which decides who can live and who must die is part of an authoritarian “tradition” of sporadic, one-off political repression that underpinned the hegemony of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) throughout the twentieth century, but also part of a globalised market economy that strips the state of some of its sovereign power and brutalises bodies, which can be exploited and killed at will. Drug traffickers and criminals move across and fight over the vast areas in which the trade in drugs, arms, and human beings takes place. These macro-criminal networks could not function without arrangements, collaborations, and collusions with state agents and entrepreneurs, making these diversified activities possible. These necropowers operate differently in each region. This is why we felt it was important to start from political ethnographies rooted in specific local realities.

How should we analyse disappearances?

Over the years, the crisis in Mexico has been presented as multiple and interlocking: first “political,” then “security,” then “humanitarian,” now “forensic” and even “funerary.” This proliferation of terms reflects the difficulty of analysing the extreme and massive violence in the country without adopting a partial vision and an analytical bias. Anthropology, and more specifically ethnography, therefore enable us to go beyond generalities and to start from lived experience to describe individual and collective histories.

There is an inevitable paradox in talking about absences. By using real-life stories of the disappeared and those who search for them, we wanted to bring body and life to cold, hard figures. This form of materialising absence through a sensitive narrative and substantial photographic work enables us to anchor a phenomenon that is essentially elusive in everyday, social life. The very act of describing the lives of people searching for the disappeared reveals the modus operandi of local violence.

Each personal story illustrates the extent to which a disappearance is surrounded by other forms of violence, both before and after, which are intertwined: domestic and gender-based violence (wife battering, incest, human trafficking, even femicide), structural violence (poverty, extractivism, discrimination, or racism), petty or serious crime (theft, extortion, kidnapping), politically motivated repression (extrajudicial executions, massacres, enforced disappearances). And then there is the institutional violence that follows disappearance and which the families of the disappeared experience head-on in their bureaucratic procedures or during their searches “in life” or “in the field.”

How does the phenomenon of disappearance reveal broader contemporary transformations, beyond the case of Mexico?

Work on violence, whether political or criminal, has been the subject of renewed attention in English-language social and political science since the 2000s, and in France since the terrorist attacks of 2015. As part of the Violence and Exiting Violence Platform hosted by the FMSH, we have spent the last five years looking at these phenomena of entry into and “exit” from violence in a comparative way, drawing on the study of previous situations of violence in Latin America (dictatorships, guerrillas, paramilitarism, etc.), Africa (militias, dictatorships, genocides, etc.), and the Middle East (wars, colonies) in order to consider more recent expressions of violence, such as jihadism in the Middle East and sub-Saharan Africa, or organised crime in Mexico.

In this context, a number of specific features stand out in the Mexican case:

- The category of “the disappeared” has globalised and expanded, and no longer refers solely to colonial or dictatorial regimes, which raises questions about the place of violence in “democratic” or “postcolonial” societies, or in societies that have undergone “democratic transitions”;

- The economy of violence is the fruit of the authoritarian tradition of the Mexican state, but also of an advanced capitalism that commodifies and devalues the bodies of victims;

- The movement to find the disappeared in Mexico intersects with the disappearance of migrants in transit through the country and the caravans of Central American mothers who search for them;

- Those who search for missing persons are mainly women, as in other mobilisations of mothers of the disappeared in Latin America, and the mother-son relationship is foregrounded in the press and in research, which tends to obscure the affective links of other women (wives, daughters, sisters) or of men (husbands, fathers, brothers, sons), who are also searching for their loved one(s).

When faced with a phenomenon of such magnitude, it is not enough to write about it in exclusively scientific books or journals.

Why write differently? Why choose a different format from the scientific book?

This choice stemmed from two key observations: The first is that in France, apart from a few solidarity groups, journalists, and researchers specialising in Mexico, few people really understand what is happening there, and attempts to explain it quickly fall into stereotypes that are reinforced and trivialised by new TV series such as Narcos. The second is that, when faced with a phenomenon of such magnitude, it is not enough to write about it in exclusively scientific books or journals. I think a lot about the place of the social sciences in society and the role they can play in understanding, and even preventing, crucial issues such as extreme violence.

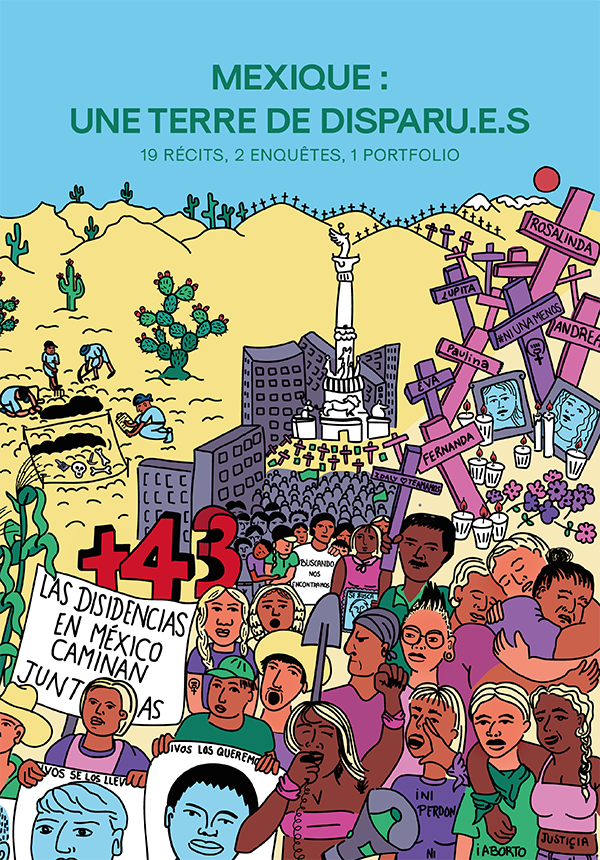

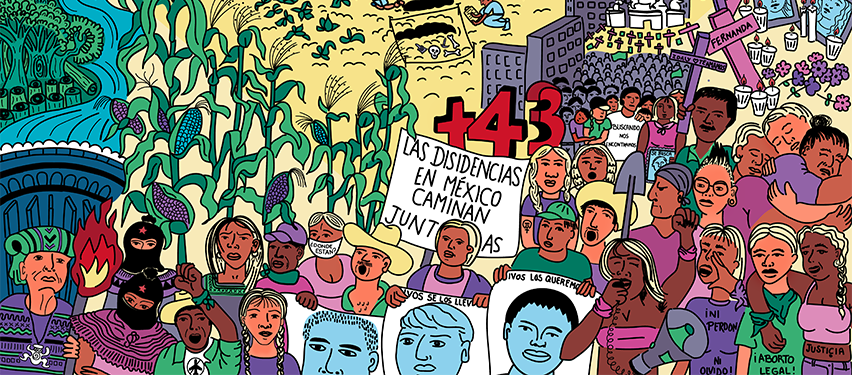

I therefore wanted to make an unattractive subject more accessible and open to a wider audience, by using a formal approach that emphasises the background. The cover and the chronological frieze were created by members of the Collectif Paris-Ayotzinapa, while the photographic work was largely carried out by the photographer Emmanuelle Corne. Together, they play a fundamental role in revealing the places and people that make up the phenomenon of disappearance and in giving body and life to figures that are all too impersonal.

I also opted for an ethnographic style of writing that prioritises the lived experience of each of the authors, hence the use of the first person singular, which makes the subject more familiar and accessible. And we all agreed to anonymise the cover and table of contents in order to emphasise the stories rather than our names, which goes against current norms for the evaluation of our research. Finally, this collective work benefited from professional layout by the FMSH’s communications department, without whom this original format would not have been possible.

This combination of choices in terms of writing style and the central place of the visual allow for several levels of reading: in addition to the ethnographies and articles with rigorous scientific content, the reader will find boxes exploring concepts or genealogies on particular themes, as well as references to other material (documentaries, books, websites, etc.) at the end of each article, and an exhaustive final bibliography. All in all, this work represents a valuable and serious tool on the subject of disappearances in Mexico and elsewhere.

As we mark the tenth anniversary of the disappearance of the Ayotzinapa students in 2024, what new role can the mook play?

On 26 September 2024, coordinated actions will take place all over the world in solidarity with the students’ parents. To mark this occasion, we are working on a new edition of the mook, of which there are only a few copies left. The Ayotzinapa case, as well as the figures and some factual information, will be updated. A Spanish version of some of the articles in the mook is also being produced and will be published in a similar but shorter format by the CEMCA publishing house, including new contributions that continue to give a voice to the buscadoras. In the meantime, in December, a delegation from the Movimiento por Nuestros Desaparecidos en México will be arriving in Paris with the support of Serapaz and various groups in France. Finally, a very fine exhibition, entitled “43,” will be held from 29 January to 19 February at Anis-Gras - Le Lieu de l’Autre in Arcueil. It will feature an artbook with beautiful pixelated masks inspired by Latin American textiles, symbolising the universality of disappearance and paying tribute to the victims of enforced disappearance.

Isela cherche son frère. Elle se repose, seule, sur les marches de la place publique après s’être rendue dans le centre de détention de la ville.

Expertise médico-légale sur le site de la Gallera.

Les familles de disparu.e.s, pour la plupart des mères, s’apprêtent à creuser à la recherche de fosses clandestines.

Cirilo cherche son fils (et l’ami de son fils enlevé avec lui).

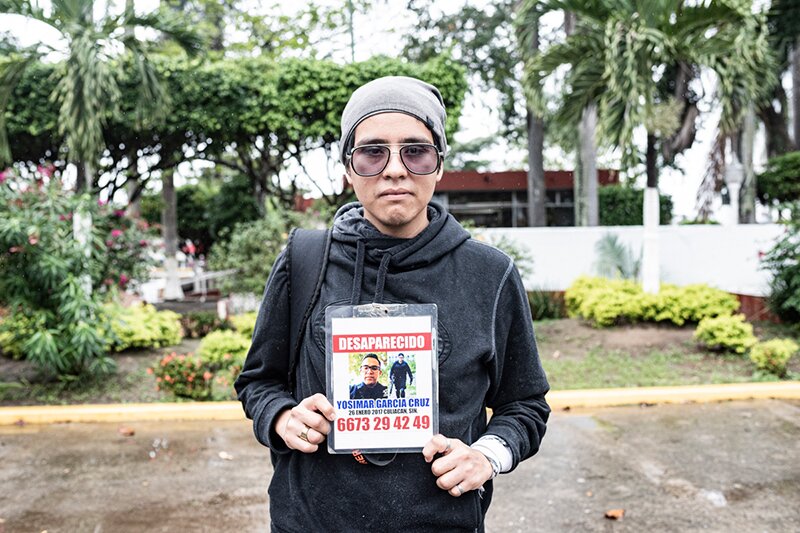

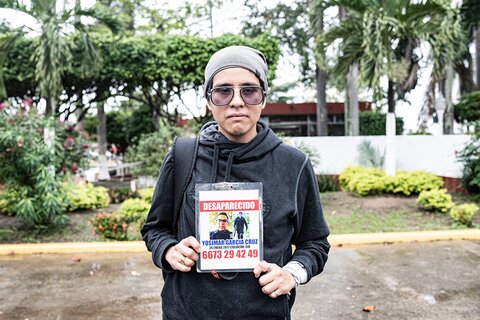

Angel a 26 ans. Il cherche son frère qui a été enlevé par ses collègues policiers.

Les portraits de mater dolorosa à la sortie de la première messe pour bénir la Ve Brigade.

Mario Vergara montre quelques os calcinés qu’il pense être des os humains au regard de leur taille et leur forme

Lina, qui cherche sa sœur, la tête dans les portraits de l’arbre de l’espoir.

Mario cherche son frère.

Le coopérisme

De la rue à la mairie

Les refus de la maternité