Interview with Nazarii Nazarov

Could you tell us a little about your background?

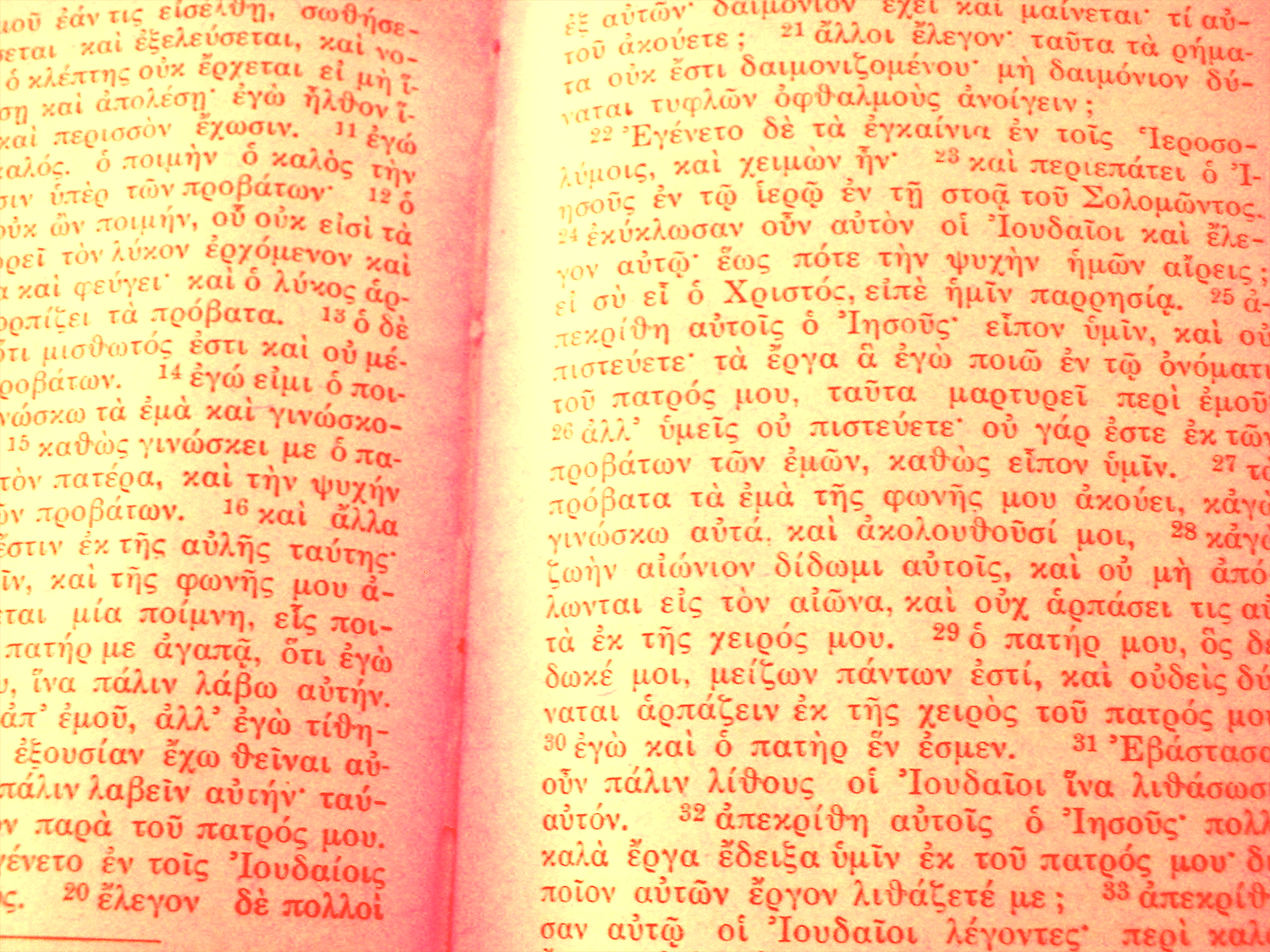

For me, poetry and science are just two aspects of my interest in language. I began writing poetry seriously when I was a teenager, and I started out in research during the last years of school, in my hometown of Kropyvnytskyi in central Ukraine. Comparing Arthur Rimbaud’s style to that of Ukrainian modernist Pavlo Tychyna, my work also investigated how the two have been translated into foreign languages. Later, in 2007, I moved to Kyiv to study and completed a degree in comparative literature at the National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy (2013). At university, I studied Ukrainian, French, English, modern and ancient Greek literature and languages. Over that period, I conducted research on Virginia Woolf, Konstantinos Kavafis (whom I translated into Ukrainian), and the reception of ancient Greek tragedy in the theater of Slavic modernism. I then decided to focus on the history of the language and wrote my PhD thesis on the history of the Ukrainian language at Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv in 2016.

I was in Paris when Russia began its all-out war against Ukraine. I then went on to work as a guest researcher at the École Normale Supérieure for over a year. Thanks to the backing of the Fondation Maison de Sciences de l’Homme (FMSH), I’ve been able to continue my research. At present, my main subjects are modern Greek dialectology, Byzantine literature, and Kievan Rus’ literature. Alongside my research, I’ve always continued to write poems and translate world literature into Ukrainian. My poems have been published in various separate collections, as well as in national magazines and anthologies in Ukraine. During the war, my work drew the interest of Norwegian poet Erling Kittelsen and we collaborated on an anthology of Ukrainian folk poetry, which was published by Norway’s oldest publishing house. It gives me great pleasure to be able to share a little of my native culture with the world and bring Ukrainian readers something new from world literature.

I spent several weeks poring through the archives and unearthing folk tales and songs, for the most part unpublished [. . .] What I managed to find in the archives of Kyiv is an incalculable treasure. I’m delighted to be able to share these discoveries with the rest of the world.

Can you tell us about the research project you’re currently working on? Why did you choose this topic?

During the summer of 2021, Oleksandr Rybalko, long-time advocate of Greek culture in Ukraine, happened to tell me that somewhere in the archives of Kyiv lay unpublished documents about the language of the Greeks of Azov, a group of dialects that have scarcely been studied and that differ from modern Greek. Since I was working on translations of both modern and ancient Greek at the time, the existence of an unexplored fragment of Greater Greece in the steppes of Ukraine presented a fascinating mystery to me. So, I spent several weeks poring through the archives and unearthing popular songs and tales, for the most part unpublished or published without adhering to philological standards. My fascination was tinged with sadness, as it was clear even back then that this language was on the verge of extinction. Today, because of the Russian imperialist war, the language’s state of preservation is unknown. The archives of Mariupol and the surrounding Greek villages are not available. What I managed to find in the archives of Kyiv is an incalculable treasure. I’m delighted to be able to share these discoveries with the rest of the world. These findings comprise several dozen fairy tales and lyrics of a hundred-odd folk songs in five dialects spoken by the Greeks of the Azov region.

What have the FMSH’s various means of support allowed you to achieve in carrying out your research project and continuing your work?

For me, the FMSH’s support constitutes an invaluable opportunity for me to continue living rather comfortably while also being able to work on projects that I started previously. I consider this support a symbol of the disinterested spirit of humanity and the profound, sincere solidarity that exists in France and Europe’s cultural arena. Every day I spend here at the FMSH, I experience this solidarity, respect, and support, as well as sincere empathy for my situation. I can’t imagine what I would do without this support. I’m sincerely grateful to the entire team at FMSH, and especially to Marta Craveri, head of International Affairs, and to Gwenaëlle Lieppe, the director of Maison Suger

As a resident at Maison Suger, what will you take away from your stay at this research residence?

It’s no exaggeration to say that Gwennaëlle Lieppe, the director of Maison Suger, pulled out all the stops to make my partner (also a Ukrainian refugee) and I feel at home here. At Maison Suger, I’ve met people from around the world involved in a variety of humanities disciplines. The monthly meetings, so kindly organized by the management, have been helping me get to know people better. Maison Suger is a place like no other, where as soon as you step out onto the balcony or go down the corridor, you can strike up a conversation about ancient Greek vase painting with a Brazilian colleague, discuss Pascal Quignard’s books with a Mexican colleague, or delve into medieval chronicles with a Belarusian colleague. It’s a very inspiring environment to work in.

For me, engaging in scientific research and translation has become an affirmation of the belief that the creative principle trumps that of destruction, and that after the most brutal of wars, through people’s united efforts, peace will always prevail.

You arrived in France to continue your research safe from the conflict in Ukraine. What can we wish you for the future?

Being exiled from a country at war is a whole different story from leaving a country at peace. Not an hour goes by without me thinking about what is happening in this war led by Russia against the Ukrainian people, against my culture and language. My life in Ukraine before the war was far from ideal, as I was already openly gay, which generated obvious communication problems, and even gave rise to considerable abuse and threats from some people, including my closest relatives. I’m still working through that trauma. But at least I haven’t had bombs landing on my head, and my neighbours in Bucha and Irpin (where I lived with my partner for two years before the war) haven’t been executed in the street; my fellow researchers at universities and the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine have not had to take up arms to defend their families and their country. In Paris, I lead a peaceful life under the invaluable protection of the French state, but I know that my Ukrainian colleagues do not have the means to work as I do. In this situation of forced migration, many of us experience this feeling of guilt. That’s why I don’t seem to have any big plans for the future: I simply want to stay alive and retain my ability to work; I want to continue working on the projects I started before the war and to start new projects. At the moment, I’m translating a novel by Huysmans, a classic French author, into Ukrainian. For me, engaging in scientific research and translation has become an affirmation of the belief that the creative principle trumps that of destruction, and that after the most brutal of wars, through people’s united efforts, peace will always prevail.

Translated and edited by Cadenza Academic Translations

Call for applications | Vice-chair of the FMSH Executive Board

The Comptoir programme

Professional equality index 2024