Mattei Dogan Prize | Interview with Jiawen Sun, 2021 laureate

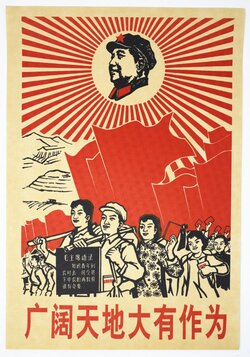

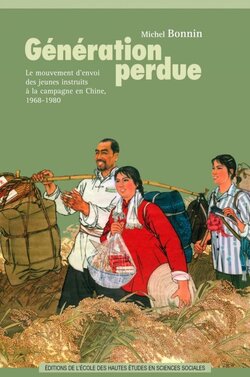

The Mattei Dogan Prize is awarded each year to two PhD theses addressing a social history subject. Jiawen Sun is the winner of the 2021 edition. She answered our questions about her career as a sociologist and her research on the former educated youth who were forced to join military farms in rural China during the Cultural Revolution. Here, she talks about her work on the members of this "lost generation", according to the expression of sinologist Michel Bonnin, and their relationship to suffering. This interview is part of the Acteurs et actrices de la recherche series that highlights the work of young researchers supported by the FMSH.

- Can you tell us about your academic background and your home institution?

From a young age, I showed talent and ability in mathematics and natural sciences, so after the university entrance examination, I entered the Department of Mathematics of Zhejiang University, which is one of the best mathematics departments in China. During my last year at the university, I realized that I was drawn to social sciences and humanities as a way to better understand human society and the norms and mechanisms that shape it. Thus, after completing my undergraduate degree, I chose to be recommended to the Department of Sociology at East China Normal University (ECNU) in Shanghai to study for a master's degree.

Fortunately for me, during my last year at ECNU, my future thesis advisor, Professor Michel BONNIN, came to Shanghai for a visit. Professor BONNIN is one of the world's leading scholars on the study of the educated youth movement in China, and I actually referred to his work for my master's thesis. The director of my dissertation recommended my research to him, so Mr. BONNIN agreed to supervise my doctoral thesis. After my arrival in France, I enrolled at the Centre d'études sur la Chine moderne et contemporaine (CECMC) of the EHESS to begin my doctoral career. Throughout my PhD, CECMC provided me with an excellent environment and academic resources and gave me a lot of help and support. In December 2020, I defended my dissertation and received my PhD in Sociology from EHESS. I am currently an associate member of the CECMC, a freelance translator (French/English/Chinese), and a contributing editor for some academic journals.

- Could you briefly introduce your award-winning thesis, "Body and Politics in Contemporary China. Sociology of suffering among former educated youths sent to military farms during the Cultural Revolution"?

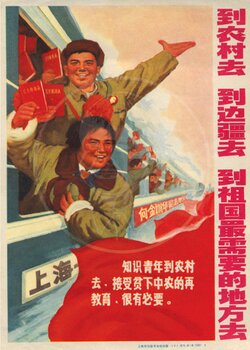

I think I should firstly introduce the Rusticated Youth Movement (lit. "Up to the Mountains and Down to the Countryside Movement") in China. This was a forced immigration movement that took place during the Mao Zedong era that spanned more than 20 years (1953-1980) and completely changed the life trajectory of about 20 million urban youth, the so-called educated youth. The initiation of this movement entailed specific political, economic, cultural and military motivations. The socialization process of an entire generation was affected to varying degrees during this movement. A number of educated youth were only 16 years old when they were sent to the countryside. They had no experience of rural life and often faced hardship and abuse from their leaders. As a result, they experienced many hardships, and some educated youth were injured, disabled or even lost their life.

By examining the life courses of the educated youth generation, I try to illustrate the production of physical pain and trauma in contemporary China and their historical, social and political origins, and to construct a unique research paradigm on the suffering experienced by educated youth. Moreover, today, the history of the Maoist era appears as a very "distant" past and is often threatened by structural amnesia and narratives to construct a "non-event". Thus, I hope to take on the "duty of remembrance" owed by contemporaries, even if it is only at my humble level.

- In what context did you decide to apply for this prize?

- Has the challenging environment of 2020 had an impact on your research?

Personally, the health situation in 2020 did not bother me much in my work. Indeed, the two most important parts of my research, namely fieldwork and collection of relevant historical documents, were completed before the outbreak. Since the second half of 2019, I have focused on writing my dissertation. Additionally, due to the outbreak, many academic databases have opened up access for browsing or downloading, making it easy for me to access the academic literature I need from the comfort of my home.

However, I had originally planned to return to China after the defending my dissertation to conduct a series of follow-up field surveys, which still seems to have to be postponed. Indeed, airline controls caused by the epidemic have delayed my return to the field, a delicate situation for a sociologist studying contemporary Chinese society. What makes me somewhat anxious is that the generation of educated youth, as witnesses of the Mao era politics, has gradually aged. So I would like to collect as many oral testimonies and memories of this generation as I could, when I still have the chance. I think they will be a very valuable asset not only for me personally, but also for future scholars studying the Maoist era in China.

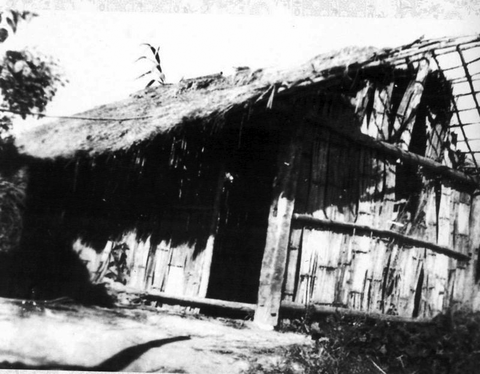

A thatched house in which the educated youth of Yunnan Production and Construction Corps live © SUN Jiawen

- What does this prize mean for you and your research ?

For me, getting this award means first of all that my research has been acknowledged by the French academic community (especially by social scientists other than sinologists), and this gives me more confidence. Since arriving in France and joining the CECMC, I have started working with one of the best groups of sinologists in France. However, before receiving this award, I never had many opportunities to present my research to scholars in other related fields. In fact, when I conceived the idea of building a sociology of suffering among the educated youth generation in China, I realized that there are feelings that resonate for all societies and cultures, such as pain, trauma, longing, sadness, etc. Therefore, one of my ambitions is to investigate, analyze, and understand the history of suffering in a broader framework, so that the suffering of the Chinese in the Mao era becomes part of the suffering of humanity as a whole. Combining Western academic theories with the specific conditions of Chinese society and drawing convincing conclusions is not an easy task. The fact that my thesis was able to be awarded by the jury of the Social History Prize proves that I am on the right path. Moreover, after receiving this prize, I think I will have more opportunities to present my research and the Rustication Movement in China to a wider audience, which I hope will make this "lost generation" more visible.

Several educated youth during the Sino-Vietnamese war (17 February-16 March 1979) © SUN Jiawen

- Is obtaining this prize a determining factor for the continuation of your research project?

I had decided long ago to pursue my research on the educated youth generation and the contemporary legacy of Mao era politics, but there is no doubt that the award has objectively provided me with great encouragement and support. This award will be a very effective "letter of recommendation" for my future academic work, whether it is to publish my doctoral thesis or to apply for research projects. Therefore, I am very grateful to the Mattei Dogan Foundation and the FMSH for awarding me this prize. Furthermore, I would also like to express my gratitude to the members of the prize jury, whose recognition is a very important encouragement for me.

An educated youth cuts down a large tree in the rainforest of Yunnan Province, where he and his colleagues will later plant rubber trees. © SUN Jiawen

Jiawen SUN

PhD - Associate Member

Centre d'études sur la Chine moderne et contemporaine (CECMC)

École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales (EHESS)

#Restitutions. Une autre définition du monde

"Plastics: A Systemic Poison" : A conference series led by the FMSH and the Tara Ocean Foundation

Semester programme | January–June 2026